NEW YORK, New York – Author Andrew Rowen retells the history of Columbus’s invasion of Española on his second voyage from a bicultural perspective in the historical fiction novel “Columbus and Caonabó: 1493–1498 Retold,” releasing on Nov. 9, 2021—the sequel to his lauded 2017 bicultural presentation of Columbus’s first voyage, “Encounters Unforeseen: 1492 Retold.”

“Columbus and Caonabó: 1493–1498 Retold” dramatizes Columbus’s invasion of Española and the bitter resistance mounted by its Taíno peoples during the period and aftermath of Columbus’s second voyage. Based closely on primary sources, the story is told from both Taíno and European perspectives, including through the eyes of Caonabó—the conflict’s principal Taíno chieftain and leader—and Columbus.

Chief Caonabó opposes any European presence on the island and massacres the garrison Columbus left behind on his first voyage. When Columbus returns, the second voyage’s 1,200 settlers suffer from disease and famine and are alienated by his harsh rule, resulting in crown-appointed officers and others deserting for Spain. Sensing European vulnerability, Caonabó establishes a broad Taíno alliance to expel the intruders, becoming the first of four centuries of Native American chieftains to organize war against European expansion. Columbus realizes that Caonabó’s capture or elimination is key to the island’s conquest, and their conflict escalates—with the fateful clash of their soldiers, cultures, and religions, enslavement of Taíno captives, the imposition of tribute, and hostile face-to-face conversations.

As battles are lost, Caonabó’s wife Anacaona anguishes and considers how to confront the Europeans if Caonabó is killed. The settlers grow more brutal when Columbus explores Cuba and Jamaica, and his enslaved Taíno interpreters witness them forcing villagers into servitude, committing rape, and destroying Taíno religious objects. Chief Guarionex, whose territory neighbors Caonabó’s, studies Christianity with missionaries and observes the first recorded baptism of a Native in the Americas but ultimately rejects his own conversion. All brood upon the spirits’ or Lord’s design as epidemic diseases ravage the island’s peoples. Isabella and Ferdinand are disturbed when Columbus initiates slave shipments home, but they deliberately acquiesce—and the justification for the European enslavement of Native Americans begins to evolve.

The new novel is the sequel to “Encounters Unforeseen: 1492 Retold,” which portrays the lives of the same Taíno and European protagonists from youth through 1492.

The new novel is the sequel to “Encounters Unforeseen: 1492 Retold,” which portrays the lives of the same Taíno and European protagonists from youth through 1492.

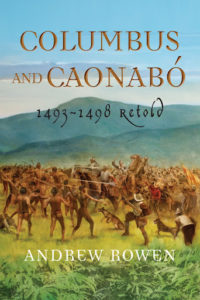

“Columbus and Caonabó: 1493–1498 Retold”

Andrew Rowen | November 9, 2021

All Persons Press | Historical Fiction |

Hardcover | 978-0-9991961-3-7 | $32.95

Ebook | 978-0-9991961-4-4 | $12.99

Paperback | 978-0-9991961-5-1 | $19.95 (releasing in 2022)

Forty-two historic and newly drawn maps and illustrations are woven into the story, including portraits or sketches of Columbus, Caonabó, Isabella, and Anacaona and de Bry engravings from the 16th century.

About The Author

About The Author

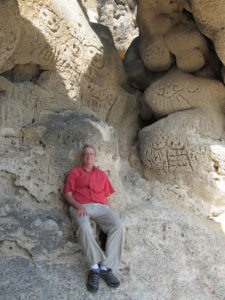

Andrew Rowen has devoted 10 years to researching the history leading to the first encounters between Europeans and the Caribbean’s Taíno peoples, including visiting sites where Columbus and Taíno chieftains lived, met, and fought. His first novel, “Encounters Unforeseen: 1492 Retold” (released 2017), portrays the life stories of the chieftains and Columbus from youth through their encounters in 1492. Its sequel, “Columbus and Caonabó: 1493–1498 Retold” (to be released November 9, 2021), depicts the same protagonists’ bitter conflict during the period of Columbus’s second voyage. Andrew is a graduate of U.C. Berkeley and Harvard Law School and has long been interested in the roots of religious intolerance.

Follow Andrew Rowen Online

Website: AndrewRowen.com | Facebook: @andrewsrowen

ADVANCE PRAISE FOR

“Columbus and Caonabó: 1493–1498 Retold”

“…fascinating. Rowen’s research into the historical record is impressively thorough…He carefully depicts what happened or may have happened (experts disagree) and…fictionalizes the perceptions, beliefs, and decisions of the European and Taíno protagonists, affording them commensurate sophistication. While unprovable, the fictionalizations are one of the book’s great strengths, stepping beyond worn stereotypes to humanize the protagonists as individuals…the book adds to our understanding of the Taínos and Contact history.”

– L. Antonio Curet, Caribbean archaeologist; museum curator. Co-ed., Islands at the Crossroads: Migration, Seafaring, and Interaction in the Caribbean

“…succeeds on two levels, as all the best historical fiction must…With meticulous research and deft phrasing, Andrew Rowen brings the 1490s to life. At the same time, he tells a great story, carrying us on a narrative journey as skillfully…”

– Matthew Restall, Seven Myths of the Spanish Conquest, When Montezuma Met Cortés

“As a leader in the Taíno community, I am often skeptical of non-Caribbean people writing about our history, culture, and customs. Many who embark on this endeavor have only skimmed through the upper layers of our written story. On the other hand, Andy Rowen takes us on a deep journey that humanizes our ancestors and treats us as equals rather than passive victims. The dialogue between the Caciques and Spaniards is intelligent, meaningful, and extremely believable…His writing invokes vivid images of events that happened long ago, credibly weaving fiction and fact! I recommend this book to anyone interested in the subject!”

– Kacike Jorge Baracutei Estevez, Higuayagua Taíno of the Caribbean

“…a feat of meticulous research, beautiful writing, and great imagination. Much of the early history of the Caribbean is irretrievably lost, but Andrew Rowen has given us a detailed and exciting glimpse.”

– Andrés Reséndez, The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America, Conquering the Pacific

In an interview, Andrew Rowen can discuss:

- Why it is important to retell the history of Columbus’s voyages from both Native American and European perspectives – Columbus’s voyages are one of history’s seminal events and part of our children’s education, but most histories of the events—whether pro- or anti-Columbus—remain focused on Columbus and European decisions and actions, i.e., the “Columbus story” or the “Spanish empire story.” But the Native peoples who opposed Columbus also made decisions and took counter actions—it’s their story, too—and presenting their perspective reminds us that the European conquest violated not only their sovereignty but their civilization’s honored ideals, traditions, and sacred beliefs. Rowen’s goal is to present both Native and European perspectives of the history, through protagonists of equivalent gravity and dignity, depicting the actions and beliefs of both peoples, all closely based on the historical and anthropological record.

- What’s retold in “Columbus and Caonabó” – It’s the first book to depict the thoughts, strategies, and actions of the Taíno chieftains who fought against Española’s invasion alongside those of Columbus and Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand. (Española is the island of the modern Haiti and Dominican Republic; the Taínos called it Haiti or Quisqueya.) It’s also the first to explore the animosity and face-to-face confrontation between Columbus and Chief Caonabó, who lead the resistance, becoming the first of four centuries of Native American chieftains to organize war against European invasion. Caonabó didn’t have the experience of the following centuries to draw upon.

- Atrocities and enslavements – Historical accuracy does involve relating the atrocities Europeans committed, the first slave shipments of Native Americans sent to Spain, and Isabella and Ferdinand’s knowledge and oversight thereof, events ignored or erased in the educations of many of us. The novel carefully traces the beginning of the evolution of the European justification for the enslavement of Native Americans.

- The initial Christian missionary efforts – Regardless of Isabella and Ferdinand’s heralding of their importance, the first baptisms on Española occurred only in September 1496, three years after the voyage sailed. The novel dramatizes the missionary effort leading to the first baptism, as well as Chief Guarionex’s (Caonabó’s equal, ruler of a neighboring chiefdom) study of Christianity with the missionaries and his rejection of Christianity.

- Epidemic disease transmission and the staggering population decline from 1493 to 1498 – The novel explores the Taíno and European perceptions (pre-Scientific Revolution) of the causes of the epidemic diseases that beset the Taínos, including the role of Taíno spirits and Christ, and the relative extent to which the staggering population decline was caused by the diseases, collapse of Taíno society and famine, Spanish brutality, and suicide. (Experts debate such today.) Columbus himself observed the population decline (as recorded in his letters to Isabella and Ferdinand), and the novel depicts his absence of sorrow or sense of responsibility—his principal concern being that the decline jeopardized gold tribute payments.

- Regardless of the decimation of Española’s Taíno population, the size and morale of Columbus’s settlement substantially deteriorated from 1493 to 1498 – Columbus’s settlement was racked by disease, hunger, his mismanagement and cruelty, and rebellion—so that, as 1498 dawns, the entire island hasn’t been conquered and resistance still boils in parts of the territory conquered. By the novel’s end, Taíno hope lingers that the European presence on the island can be contained, if not eliminated, and Caonabó’s wife Anacaona emerges to become a leader.

An Interview with Andrew Rowen

In 2017 when you released your first book, it was the 525th anniversary of Columbus’s first voyage. Why is it still important for people to understand 1492 and its aftermath, and what do your novels add to our understanding?

The collision of European and Native American peoples that began in 1492 influenced the establishment of—and is fundamental to understanding—the world and societies we live in today. The history of the collision is neither just “a Columbus story,” “a Spanish empire story,” or a “European colonial usurpation story,” but the story of the collision of two proud civilizations—with different social norms and traditions, moral beliefs, and religions. My books are an attempt to tell both sides of that broader story and contribute to a more fulsome appreciation of it. The history includes enslavements and atrocities, and my books depict them based on the historical record.

Can your two novels be read independently?

Yes. I wrote them to be readable independently because there may be different audiences. “Columbus and Caonabó” depicts events from September 1493 to April 1498 that many people don’t know much about—Columbus’s invasion of Española and the initial Taíno resistance. Its first chapter contains the information a reader of the book needs to understand about both peoples prior to 1493.

“Encounters Unforeseen” dramatizes the lives of the same Taíno and European protagonists prior to their encounters in 1492—their childhood educations, love affairs and marriages, rises to power or prominence, and religious beliefs in creation and man’s origin—and then their astonishment, fears, and objectives in 1492 and 1493. It’s a deeper bicultural dive into a history most people think they already know.

Why did you choose to write the series as historical fiction rather than historical nonfiction?

I’ve written both as historical novels for two reasons. In my view, they had to be novels because the Taínos had no written history and a novel’s greater speculative latitude was necessary to achieve commensurate dignity and gravitas of the Taíno and European protagonists. Just as important, I wanted to write them as novels so that readers could experience the encounters through the eyes of each protagonist, not merely understand events.

I try to present each participant’s actions and thoughts consistent with my interpretation of the historical record to the extent one exists and—to the extent not—as I speculate likely could have occurred, fictionalizing detail. I stick to history rather than inventing an overarching literary story plot.

What research have you done?

What research have you done?

I’ve spent 10 years researching the primary accounts written by the conquering Europeans who witnessed the events, knew the participants, or lived in the 16th century (to the extent credible) and, as they had no written history, studies of the Taínos by modern anthropologists, archaeologists, and other experts. The book contains a fulsome Sources section citing authorities and discussing interpretations of historians and anthropologists contrary to my presentation and issues of academic disagreement.

My research also included extensive onsite investigation, visiting the sites in Haiti, the Dominican Republic, Spain, and other places where the protagonists lived, met, or fought. The onsite investigations both added to my understanding of the historical record and inspired creating scenes in the novel.

What can you tell us about the title characters of “Columbus and Caonabó”?

Caonabó was the supreme chief of Maguana, one of the six principal chiefdoms of Española in 1493. He had risen to chieftain before 1492 by virtue of his ability and valor in repelling Caribe raiders, and he was the first chieftain to recognize that the Europeans came to conquer and had to be expelled from the island. In Columbus’s own words, Caonabó was “the most important chief on the island and the most courageous and most ingenious;” “no one is bolder or more daring in war;” and “all the island’s chiefs watch what he does closely and no longer have any fear, being emboldened by his killing of Christians.”

One of history’s most controversial figures, Columbus was a sincerely religious Genoese commoner who rose to be a merchant, an expert mariner, and then nobleman. In the period 1493–1498, he doesn’t understand his geographical theory that one could sail directly from Spain to Cathay (shared by some others in his time) was wrong, and he believes in the right of a conqueror to enslave the conquered (a view shared by some others in his time). The novel traces his anguish and struggle to prove his geographical theory, find gold and Cathay, and bring slavery (in gold’s absence) to Española during this period, as well as his severity with his men and their rebellion.

How does “Columbus and Caonabó” stray from traditional Columbus narratives? Have you made any historical interpretation that is new or different?

Obviously, the novel differs in concept—presenting the Native story and civilization side by side with the European. Taíno resistance is not the focus of existing historical works.

The book is very complete thematically, presenting in one book a depiction of the political, social, and religious dimensions of the conflict, as well as the disease transmission and population decline.

I believe my depictions of Columbus’s actions and his men’s atrocities generally reflect the most current research.

Did you learn anything surprising while researching this time period?

I’ve researched the period and events in primary and secondary sources for 10 years now. While I’m occasionally surprised by specific events or thoughts I stumble upon in these sources, my abiding surprise is the extent to which my boyhood education unqualifiedly professed a rightfulness in Columbus’s invasion and the superiority of European beliefs and ignored or erased the atrocities committed.

How did the Taino people fight back against the settlers?

The Taínos’ principal weapons were spears, arrow-slings, bow and arrows, and wooden clubs. The Europeans had spears, swords, crossbows, muskets, cannons, a small cavalry of horsemen with lances, and twenty attack dogs.

What atrocities did Columbus’s men commit?

Collectively, Columbus’s men forced Taínos into servitude, raped them, destroyed their religious objects, and, when making reprisals against Taíno resistance, enslaved them, burned them at the stake, and butchered non-combatants.

How many slave shipments did Columbus send to Spain during the five-year period that the novel covers? Who were the enslaved? What happened to them?

Four shipments, involving about roughly eight hundred indigenous people. The first was of about two dozen Taínos and Caribes taken aboard in the Lesser Antilles—Guadeloupe and St. Croix—on the voyage to Española, largely with the intent they be trained in Spain to serve as interpreters and assist missionaries when returned to Española. The other shipments were largely of Taínos captured on Española, shipped to be sold into slavery in Spain to finance the settlement. However, at Isabella and Ferdinand’s order, their sale was conditional, pending a determination by theologians and lawyers whether enslavement of Indians was permissible—which determination wasn’t made during the period of the novel. Many died of European diseases on the ocean crossings to Spain, and many others died of diseases in Spain, either awaiting or after sale.

Columbus’s men in Española also took an unrecorded number of Taínos as slaves for themselves.

What was Isabella and Ferdinand’s reaction to the slave shipments?

In 1493, Isabel and Ferdinand anticipated that the “Indians” on Española would become their vassals upon the island’s conquest, not their slaves or slaves to Española’s European settlers. From 1493–1498, they consistently denied Columbus’s repeated requests to institute a general slave trade of indigenous peoples. But slavery existed on certain permitted bases in Spain and court financiers were interested in financing overseas conquests by selling conquered peoples. As the woes and financial losses of the Española settlement grew, Isabella and Ferdinand permitted the sales of the captives shipped but imposed the condition that the sales be subject to theologians and lawyers determining permissibility. In 1496, they acknowledged that war captives could be sold.

One of the stated purposes of Columbus’s second voyage was to bring Christianity to the natives. How did you depict the missionary effort and the first baptisms?

Of the 1,200 sailing on the second voyage, about a dozen were missionaries. Their leader, whose appointment was affirmed by Pope Alexander VI, deserted his post in 1494, and the first baptisms of Taínos on Española didn’t occur until 1496. Most contemporary observers, including Columbus and the famous chronicler Bartolomé de las Casas, thought the effort was meager.

That said, there were a few missionaries with genuine zeal, in particular a friar Ramón Pané, a Catalan. I wrote a number of scenes envisioning how Pané tried to surmount the language barrier to teach, how the first baptism unfolded, and Pané’s instruction of the Taíno chieftain Guarionex in Christian doctrine. Guarionex was renowned for his wisdom of the Taínos’ religion and spirits, and he rejected Christianity.

How did you research and depict the staggering Taíno population declines?

I read the views of historians, population experts, and epidemiologists, who continue to debate the basic magnitude and causes of Taíno death. Much is not agreed and speculative. There’s substantial disagreement over the size of Española’s indigenous population at the invasion’s inception—estimates generally range from one hundred thousand to eight million. Experts also debate the relative extent that its decline should be attributed to Spanish brutality (warfare and the harsh conditions of servitude and slavery), the collapse of the indigenous social system occasioned thereby (famine, flight to remote areas, and suicide), or the ravage of European diseases, and epidemiologists offer varied analyses of the diseases transmitted.

I don’t try to answer these questions, but the novel presents my interpretations or speculations of the protagonists’ perceptions of the underlying answers.

“Columbus and Caonabó” includes 42 historic or newly drawn maps and illustrations. Tell us about them.

There’s a newly drawn sketch of Caonabó set beside a historic portrait of Columbus, as well as portraits of Isabella and Ferdinand and a newly drawn sketch of Anacaona. There also are newly drawn maps to show where events took place, and the routes Columbus took at sea are marked on historic maps that were drawn between 1500 and 1516. There are famous de Bry engravings depicting the Spanish conquest of Española and elsewhere, woven into relevant scenes.

What is your opinion of Columbus? Should Columbus Day be celebrated?

In my books, I try to be analytical and portray what each Taíno and European protagonist—including Columbus—did and thought as validly as I can determine or speculate based on research of the historical record. I also try to present each protagonist’s thoughts within the context of his or her 15th century perspective and to leave moral judgments to each reader.

Columbus did have admirable qualities—perseverance through adversity, rising from a humble origin to nobility, and great skill as a mariner—and many scenes in my books depict those qualities. But he violated the sovereignty of and enslaved Native peoples and men under his command committed atrocities—all facts recorded by contemporaneous chroniclers. The latter actions often are excused on the basis that Columbus was simply a European man of his times; but regardless, from our 21st century perspective, as well as the 15th century Taíno perspective, Columbus did many bad things.

In my view, federal and state governments shouldn’t observe Columbus Day because doing so honors a historical figure whose legacy—while foundational to our present civilization and possessing some qualities and heritages we admire—is eviscerated by invasion, enslavements, and atrocities we and our governments in the 21st century condemn. Indigenous People’s Day should be celebrated instead. Non-observance of Columbus Day doesn’t deny his role in history; it reflects that our societies have progressed beyond honoring his legacy.

What’s next for you?

There will be at least one more sequel.

PRAISE FOR ANDREW ROWEN’S FIRST NOVEL,

“Encounters Unforeseen: 1492 Retold”

“Amazing! The lives, loves, victories and defeats of the Taíno Indians are just as meticulously and poignantly brought to life as Columbus, his famous voyage and Queen Isabel’s court. A sprawling, globe-trotting, all-consuming tour de force illuminating all sides of the epic cultural clash that created the New World.” – Trey Ellis, Platitudes, Home Repairs, Right Here, Right Now

“The encounter of Columbus and Native Caribbean peoples set in motion events that created the modern world. History books provide brief accounts, but what was the Encounter really like, what did it mean, how was it expressed, in simple, human terms? Andrew Rowen transports us to this moment of creation, and does so by tracing the lives of the main protagonists. This is a fascinating story of enmeshed lives, and the consequences of new worlds. It is written with scrupulous detail to historical accuracy, and, even knowing how it will end, the prose is an imaginative and entertaining portrait of a past we could not otherwise experience.” – William F. Keegan, Curator of Caribbean Archaeology, Florida Museum of Natural History, Talking Taíno, Taíno Indian Myth and Practice

“Rowen’s research—a combination of scholarly investigation and travel conducted over six years—is nothing less than breathtaking. The sensitivity and originality of his portrayals are equally impressive, avoiding the trap of simply retelling a familiar tale from an exclusively European perspective or casting the explorers as nothing more than rapacious colonialists…A remarkably new and inventive take on a momentous episode in the 15th century.” – Kirkus Reviews

A former award-winning journalist with national exposure, Marissa now oversees the day-to-day operation of the Books Forward author branding and book marketing firm, along with our indie publishing support sister company Books Fluent.

Born and bred in Louisiana, currently living in New Orleans, she has lived and developed a strong base for our company and authors in Chicago and Nashville. Her journalism work has appeared in USA Today, National Geographic and other major publications. She is now interviewed by media on best practices for book marketing.