BEIRUT, Lebanon – In her upcoming memoir, Amal Ghandour reflects on her life as a privileged member of the “silent” Arab generation that came of political age in the 1980s, seeking clarity from a twin excavation of the self and the world that gave shape to it. In doing so, she draws from personal histories and larger political and cultural trends to thread a generational tale of seeming early promise, cascading defeats, and devastating finales.

BEIRUT, Lebanon – In her upcoming memoir, Amal Ghandour reflects on her life as a privileged member of the “silent” Arab generation that came of political age in the 1980s, seeking clarity from a twin excavation of the self and the world that gave shape to it. In doing so, she draws from personal histories and larger political and cultural trends to thread a generational tale of seeming early promise, cascading defeats, and devastating finales.

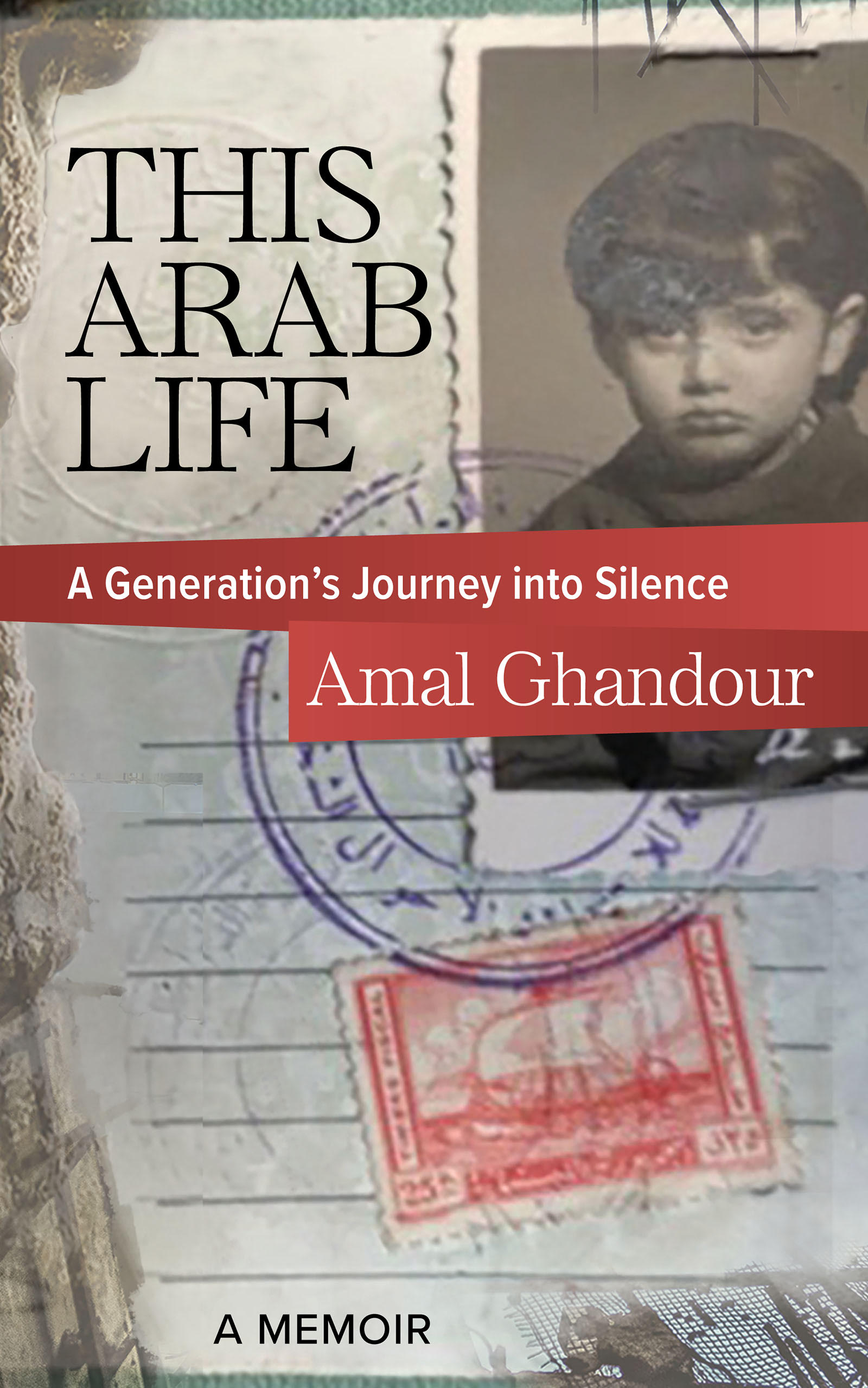

“This Arab Life: A Generation’s Journey into Silence” (Bold Story Press, Oct. 11, 2022) unfolds through a series of juxtapositions of private tragedies and epochal events, places and geographies, characters and lived experiences, innermost truths and shared realities. Through such depictions, the author pulls together half a century of Levantine and Arab history, even as she proceeds to disentangle it for answers.

“This Arab Life” begins in Amman in the summer of 1973 and concludes in Beirut in December 2021. But the narrative encompasses a world by turns distant and faded, near and vital.

“This Arab Life: A Generation’s Journey Into Silence”

Amal Ghandour | Oct. 11, 2022 | Bold Story Press | Non-fiction/Memoir

Advance Praise

“Unsparing of herself as ‘informant,’ in a book that is at once painful and a delight to read, Amal Ghandour probes the conscience and circumstances of a small but very influential section of Arab society. Stylish, witty and heartbreaking, this is a unique and critical contribution to our current soul-searching.”

– Ahdaf Soueif, best-selling Egyptian novelist and short story writer, and political and cultural commentator

“Amal Ghandour has written a nostalgic book with glimmers of brilliant personal, social and political observations and probing about Jordan and Lebanon, about wars and longings, about a rich life of upheavals and laments.”

– Raja Shehadeh, Palestinian writer and lawyer, and founder of the human rights organization Al-Haq

“This Arab Life is a sweeping retrospective on a generation’s historic complicity in the present travails plaguing the Arab world. The book is, at once, intimate, far-reaching, political, angry, melancholic, funny, and nostalgic. Ghandour’s reflections on her life, and on the decisions taken by her and her peers as they came of age in the eighties and nineties, offers important insight for anyone seeking to understand how we got to where we are today in the region. The book is a cautionary tale of political acquiescence, and one that is, like many Arabs, stuck between an urgent impulse to act, to change, to hope, alongside an overwhelming sense of despair and apathy.”

– Tarek Baconi, author of “Hamas Contained: The Rise and Pacification of Palestinian Resistance,” and president of the board of al-Shabaka: The Palestinian Policy Network

“The Arab world hasn’t fallen into silence. It has descended, not unlike other parts of the globe, into a logorrhea of reflexive grumbling, vacuous politics, and hopeless nostalgia. Amal Ghandour’s voice pierces through this noise: analytic, female, rebellious, acid yet soothing, if only because so much of the corrosion she describes is just begging for her brand of intellectual rust remover. Ghandour taunts the very elites she belongs to with questions few of the privileged ever ask themselves: Wealth aside, what is our worth? Who are we, as an elite, if we do little more than indulge and free-ride? Her own answers rise from a unique blend of acute insights, touching vignettes, and downright introspection, all caught up in the region’s traumatic historical arc, and bound together by Ghandour’s ever so tight, elegant style.”

—Peter Harling, founder of Synaps, a public interest research Institute

About the Author

Amal Ghandour is the author of “This Arab Life: A Generation’s Journey into Silence” (Bold Story Press, Oct. 11, 2022). Her career spans more than three decades in the fields of research, communication, and community development. An author (“About This Man Called Ali”) and a former blogger (“Thinking Fits”), Ghandour is Senior Strategy Adviser to Ruwwad al Tanmeyah, a regional community development initiative, a position she has held since 2009.

Amal Ghandour is the author of “This Arab Life: A Generation’s Journey into Silence” (Bold Story Press, Oct. 11, 2022). Her career spans more than three decades in the fields of research, communication, and community development. An author (“About This Man Called Ali”) and a former blogger (“Thinking Fits”), Ghandour is Senior Strategy Adviser to Ruwwad al Tanmeyah, a regional community development initiative, a position she has held since 2009.

Ghandour was special adviser to Columbia University’s Global Centers, Middle East, from 2014 to 2017, sits on The Women Creating Change Leadership Council of Columbia University’s Center for the Study of Social Difference; the Board of Trustees of International College, Lebanon; the Board of Directors of Ruwwad, Lebanon; The Board of Directors of Synaps, a public interest research institute; and has served on the Board of Directors of The Arab Human Rights Fund (2011-2014). She holds an MS in International Policy from Stanford University and a BSFS from Georgetown University.

Follow Amal Ghandour on social media:

Twitter: @ghandour_ag | Instagram: @amalghandour

In an interview, Amal Ghandour can discuss:

- Countering stereotypes about Arab women and their condition

- The importance of native Arab voices in narratives about the Arab world

- Understanding the meaning and lasting impact of the 2011 Arab uprisings

- The current moment in the Arab world and the political and cultural trends sweeping through it

- The collapse of Lebanon and its implications

- Islamism and its place in Arab politics and culture

- Straddling writing genres – including elements of memoir, cultural commentary along with historical and political context

An Interview with Amal Ghandour

How does “This Arab Life” differ from other memoirs by Arab women?

There aren’t many memoirs written in English by Arab women. Iranian women have been more visible on that front. But invariably, theirs (Arab and Iranian) are personal tales of persecution and struggle, escape or deliverance. In the case of translated older generation activists like Egyptian Nawal el-Saadawi, there is, of course, the noble cause-focused memoir.

“This Arab Life” stands this tradition on its head. Strictly speaking, it is not a memoir. It bestrides genres and the personal in it is to illuminate a larger generational story. It is written by a privileged woman and casts a sharp lens on the elites and their place in this story, tracing a journey of grand possibilities and wholesale abdication.

Were you aware of any stereotypes and tropes about Arab women that you wanted to stay away from in your writing?

I am always alert to stereotypes and tropes about women, both homegrown and foreign. But in writing “This Arab Life,” I didn’t set out to avoid or focus on any. I wanted them to reveal themselves naturally through what I witnessed and experienced as an Arab woman. For example, the growing influence of Islamism in the 1970s, when we were still teenagers, and how that began to change our world: the social norms, the dress codes, the personal status laws, the dos and don’ts.

I dedicate a couple of pages to the veil because of the extraordinary significance it has been accorded in the contrived cultural wars between the East and the West. I wanted to enrich the discourse with the nuance and humanity that suffuse our realities but are almost always absent in the furious back and forth. And I thought it’s important to show how we women (and inevitably the veil) have been conveniently weaponized by both sides.

You went to the United States when you were a teenager to do your high school and university studies, and then back to Jordan, where you grew up. How would you describe that experience of voyage and return?

Going to the U.S. for university studies was the norm for many middle and upper-class Jordanians. I went in the 11th grade, earlier than my friends, because of family circumstances. High school in the U.S. is like an early ticket into the American way of life. At the tender age of 15 or 15, you imbibe very quickly the culture and its quirks, the politics, the language, the habits… By the time I graduated from Holton Arms and was ready to join Georgetown’s Foreign Service School, I was intimately familiar with America and very much at ease in it.

America was an education. It was social freedom and political loneliness on issues like Israel and Palestine, for example. It was a mélange of unexpected friendships and fascinating encounters with political and intellectual adversaries. It was adulthood.

Returning was easy – at least for me. Amman was a cocoon, and cocoons, by their very nature, are cozy and comfy and safe. We knew the rules and most of us played by them.

In your book, you choose to reveal Lebanon, your birthplace, through dichotomies and juxtapositions. In one of them, you describe yourself as “the tourist.” Where did that come from?

The label was bestowed on me by some Lebanese friends who remained in Lebanon during the 1975-1990 civil war. Postwar, there was a rupture of a sort between those who stayed and those who left. I never, in fact, lived in Lebanon before 1991, so the tension was perhaps deeper.

For many of those who stayed, those who left were foreign to Lebanon and its mysteries, didn’t quite love and understand it, and didn’t have the right to criticize it because they had abandoned it. Every time I offered a critical perspective about any matter Lebanese, the comeback was, what do you know – you, the tourist?

So I use the term as a literary device to unpack Lebanon and its many paradoxes for the reader.

Connection is a theme that runs throughout your book. Connection with your family, connection with your culture and connection with yourself. Why was this important for you to write about?

Because much of contemporary history in the Levant and other corners of the Arab world (Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, Palestine, Iraq, Egypt, Libya, Yemen…) has been that of uncertainty, dislocation, displacement, and disruption. Continuums and connections offer context, color, perspective, anchor. They help you locate yourself in the sweep of history, if you like.

I am not referring here only to the costs of political turmoil and war. Environmental degradation, modernity’s reckless assault on heritage, oppressive regimes’ intolerance of the lushness of culture. Your world becomes very lonely without connections, and hence my quest for them.

How did your educational and professional backgrounds influence your writing?

Politics, culture, and social themes permeate my writing – my old “Thinking Fits” blog, my first book, the pieces I chose to write for various publications, “This Arab Life”… My work as a journalist after graduation and my communication and community development career have given me invaluable insight into life outside the narrow borders that keep many of us in the Arab world in our tiny bubbles. Such insight naturally informs everything I do and write.

You straddle genres in your book, combining elements of memoir, history and cultural commentary. Did you find it difficult to insert your own voice into your writing, especially given your research background? How would you describe the tone of your writing?

I found it interesting and challenging, actually. Inserting my voice was not hard, because I had a personal story to tell. The question was how much of myself would I dare share. I decided that I would simply write with abandon and then see what I might want to delete.

But I did have to resist the habit of seeking support in quotations and citations. I worried about the disruption to the narrative that a seemingly academic tilt might cause. So, I minimized those to ones essential to the argument. I am hoping that the two styles danced well on the page.

Some people label the 2011 Arab uprisings as a “failure” – how do you see them?

In this opening act, I saw them as failures – both for the people and the regimes. And the consequences have, of course, been devastating. We have countries that have been dismembered, cities that have been laid to waste, regions that have been cleansed, entire generations that have been traumatized… Chasms checker the Fertile Crescent and vacuums poke it. Yemen does even worse, and North Africa is only modestly better.

But the uprisings have offered extraordinary lessons and revelations as well. Perhaps the most important among them is the real difficulty of dislodging police states.

You cover a lot of ground in your book. Are there any stories or experiences that were left on the cutting room floor that you wish you could have included?

Many. But I am happy for them to stay on the cutting floor. As I wrote in “This Arab Life,” my stories are excavations at their most delicate, and the introspections are constantly hiding frailties and awkward matters of the heart and mind. I shared all that I could share – for now.

Can you tell us about your previous book, “About This Man Called Ali?”

The book is a historical narrative of the contemporary Near East through the life and art of Ali al Jabri, a magnificent but rather obscure Syrian artist who was murdered in Amman in 2002. Ali was a dear friend, and when he died I thought who he was, how he lived, what he painted, and what he wrote in his diaries would offer very original insight into our modern history.

What do you hope readers take away from reading your new book?

Many things, I am hoping.

A knowledge of people, place, and time that is intimate. I hope I have succeeded in weaving a history from below for the reader.

And for decades, we Arabs have heard a painful description of us: Arab Exceptionalism. It became very popular after the revolutionary fervor that swept through East Europe in 1989 and seeming transitions to democracy elsewhere. A truism about us Arabs took root: that we are resistant to progress, stuck, incapable of renewal. My generation came of political age in the 1980s. Our silence was part of that narrative. In “This Arab Life,” I offer my own narrative about what transpired. I wrote to achieve clarity and build contexts. My hope, again, is that the reader has achieved the same when done with “This Arab Life.”

What’s next for you?

Another book. A new blog. More writing.

A former award-winning journalist with national exposure, Marissa now oversees the day-to-day operation of the Books Forward author branding and book marketing firm, along with our indie publishing support sister company Books Fluent.

Born and bred in Louisiana, currently living in New Orleans, she has lived and developed a strong base for our company and authors in Chicago and Nashville. Her journalism work has appeared in USA Today, National Geographic and other major publications. She is now interviewed by media on best practices for book marketing.