David Mura unmasks how white stories about race attempt to erase the brutality of the past and underpin systemic racism in the present

David Mura unmasks how white stories about race attempt to erase the brutality of the past and underpin systemic racism in the present

Minneapolis, MN – David Mura grounds his work in historical and fictional narratives that whiteness tells society in order to uphold systems of oppression in The Stories Whiteness Tells Itself (Jan. 31 2023, University of Minnesota Press).

Intertwining history, literature, ethics, and the deeply personal, Mura looks back to foundational narratives of white supremacy (Jefferson’s defense of slavery, Lincoln’s frequently minimized racism, and the establishment of Jim Crow) to show how white identity is based on shared belief in the pernicious myths, false histories, and racially segregated fictions that allow whites to deny their culpability in past atrocities and current inequities. White supremacy always insists white knowledge is superior to Black knowledge, Mura argues, and this belief dismisses the truths embodied in Black narratives.

In his cogent analysis of white historical, fictional (Faulkner), cinematic (Spielberg) and journalistic narratives, Mura points to the persistent trauma racism has exacted; he lays bare how deeply we need to change our racial narratives—what white people must do—to dissolve the myth of Whiteness and fully acknowledge the stories and experiences of Black Americans.

The Stories Whiteness Tells Itself: Racial Myths and Our American Narratives

David Mura | Jan. 31, 2023 | University of Minnesota Press | Nonfiction

Paperback | ISBN: 9781517914547 | $24.95

Ebook | $24.95

About the Author

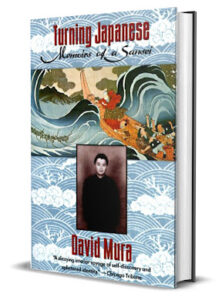

David Mura is an essayist, memoirist, poet and fiction writer who brings a unique perspective to our multi-racial and multi-cultural society. A third-generation Japanese-American, he has written intimately about his life as a man of color and the connections between race, culture and history. In public appearances interweaving poetry, performance and personal testament, he provides powerful insights into the racial issues facing America today.

David Mura is an essayist, memoirist, poet and fiction writer who brings a unique perspective to our multi-racial and multi-cultural society. A third-generation Japanese-American, he has written intimately about his life as a man of color and the connections between race, culture and history. In public appearances interweaving poetry, performance and personal testament, he provides powerful insights into the racial issues facing America today.

Mura’s memoirs, poems, essays, plays and performances have won wide critical praise and numerous awards. Their topics range from contemporary Japan to the legacy of the internment camps and the history of Japanese Americans to critical explorations of an increasingly diverse America. He gives presentations at educational institutions, businesses and other organizations throughout the country. You can find him at his website: http://www.davidmura.com/

Follow David Mura on social media:

Facebook | Twitter | LinkedIn

In an interview, David Mura can discuss:

- How white-dominated narratives of America’s past and present are deeply intertwined with our racist history – This can be seen in not only our historical texts and myths, but also in fiction, film or everyday racial incidents like the killings of Philando Castile and George Floyd by police, both of which happened just a few miles from David’s home in Minneapolis.

- How America began with two goals – one was equality, freedom and democracy; the other was the establishment and maintenance of white supremacy. White America is fine with telling the story of America through the lens of the first goal, but not through the second.

- His identity as a third generation Japanese American and how that identity informed his writing.

- How readers can overcome psychological denial and engage more deeply with the struggle for racial equality.

- The overly simplistic and superficial view of white supremacy and the legacy of slavery in the U.S., plus the lasting effects of the Reconstruction Era.

- What we can learn from activist and writer James Baldwin about racism in America

- How America would be different if schools put greater emphasis on the stories and experiences of all Americans, rather than just white-dominated narratives.

- His friendship with novelist Alexs Pate and his involvement with The Innocent Classroom program that trains K-12 educators to improve their relationships with students of color.

Praise for The Stories Whiteness Tells Itself

“The Stories Whiteness Tells Itself is the book I wish I could have been handing out during the height of the Black Lives Matters protests. There are many works written about the overarching effects of White Supremacy in America, but what’s essential about this book is the clarity provided by the wisdom and holistic vision of David Mura. The Stories Whiteness Tells Itself is the rare book that pulls off the magic trick of taking an incredibly explosive issue and disarming it with such grace as to make elusive truths feel suddenly accessible.” — Mat Johnson, author of Pym, Loving Day, and Invisible Things

“A powerful meditation on the conscious and unconscious effects of racist narratives. Anyone who’s lived through the last three years of racial reckoning and is wondering how we got here and where we go next will find this book useful.” — Shannon Gibney (waiting for attribution preference) Dream Country

“With this collection of taut essays, David Mura holds searing light on the epistemology of Whiteness, interrogating the brutal creation and lethal maintenance of this alibi rigged to serve as an identity. Mura, with painstaking patience half-masking anger and grief, offers what so many white Americans claim they want; what so many of the rest of us tire of providing: a rigorous education in perceiving themselves stripped of their dearest myths. I push back on the author’s use of “blindness” as metaphor over the book’s arc, a way the sighted shorthand an inability to perceive. No. For what Mura argues with compelling intelligence is that most white people willfully ignore history and resent being reminded of their place within its present. I suspect some will, as always, manage to ignore this entry into a tradition that includes Baldwin, Morrison, Hartman, and Wilderson; but those who heed it will find themselves fortified for change.” — Douglas Kearney, National Book Awards Poetry finalist

“More than anything, David Mura reminds us that history is still just a story, and life and death lies in who gets to tell it and what’s been told. This is a re-examination of the American imagination itself and the myths we need to dismantle for a proper foundation to finally grow. It’s fearless, illuminating, and revolutionary” — Marlon James, winner of the 2015 Booker Prize

“The vitriolic discourse against educators and librarians displays the resurgence of overt hostility toward books, in particular stories coming out of marginalized communities. Books written by writers of color and writers writing about how race is experienced by people of color are accused of teaching people to hate America. Meanwhile, there is The Stories Whiteness Tells Itself. David Mura, a gifted Japanese American writer and storyteller is in conversation with gifted African American writers/prophets such as Baldwin, Morrison, Gates, Kendi, and his friend and contemporary Alex Pate, author of the novel Amistad. Together, Mura and the thinkers he’s enlisted serve to shore up the experiences of people of color against the gaslighting we face and provide Whiteness with an opportunity to engage with fuller stories that could bring it out of a ‘distorted reality’ where ‘the oppressor thus lies to himself both about himself and about those he oppresses.’” — Sherrie Fernandez-Williams, author of Soft: A Memoir

Additional Praise for David Mura

“Upon finishing this book, I think that we will no longer be strangers. We will no longer feel that we are on our journey alone. This book is the intersection where our paths meet, where we can forge bonds that transcend the racial divide. Maybe from here on out, we can accompany each other on our journeys as friends and fellow artists, but most importantly, as fellow humans.” — Reyna Grande, Author of The Distance Between Us

“Upon finishing this book, I think that we will no longer be strangers. We will no longer feel that we are on our journey alone. This book is the intersection where our paths meet, where we can forge bonds that transcend the racial divide. Maybe from here on out, we can accompany each other on our journeys as friends and fellow artists, but most importantly, as fellow humans.” — Reyna Grande, Author of The Distance Between Us

“A Stranger’s Journey is an essential work of literary criticism and memoir, challenging readers and writers alike to think about writing, race, and identity in new ways.” — Rebecca Hussey, Foreword Reviews

“There is brilliant writing in this book, observations of Japanese humanity and culture that are subtly different from and more penetrating than what we usually get from Westerners.” — The New Yorker

“There is brilliant writing in this book, observations of Japanese humanity and culture that are subtly different from and more penetrating than what we usually get from Westerners.” — The New Yorker

“This intimate memoir of a third-generation Japanese American’s foray into the land of his ancestors is more than a colorful travel journal. And it is more than the story of one man’s search for his cultural place in the world when for the first time he is surrounded by faces all looking like his…David Mura has made his first book something rarer—a brutally honest, beautifully written meditation on art, race, country, sexuality and marriage, and ultimately…the exploration of himself as a man…This book is the powerful record of all he saw and experienced [in Japan] written with a poet’s eye and a memory for what was never there.” — Joyce Howe, East Bay Express

An Interview with David Mura

Your hometown of Minneapolis became a focal point for the Black Lives Matter movement after the police killings of Philando Castile and George Floyd – how were you affected?

My book begins with an essay on the police murder of Philando Castile and ends with an essay on the police murder of George Floyd. Both these police killings took place a few miles from my home. My son works in a school less than a mile from Cup Foods and he knows Darnella Frazier, the brave 17-year-old who took the video of Floyd’s murder, and he went to school with the EMT who tried to intervene and save Floyd. My daughter, sons and I all participated in the demonstrations against the killing of Floyd in the neighborhood where my children grew up and went to school.

In 2021, with African American writer Carolyn Holbrook, I co-edited and introduced an anthology of MN BIPOC writers, We Are Meant to Rise: Voices for Justice from Minneapolis to the World, and many of the writers, including my daughter, wrote about Floyd’s murder and the subsequent protests. The anger, sadness, analysis, and diverse personal testimonies in that book reflect the activist and artistic community here that I’m proud to be a part of, and the reverberations from these murders and demonstrations have had national and international consequences.

Why and how did you come to write this book about the dialogue and struggle between white and Black Americans, given that you yourself are a Japanese American?

Both my parents, at ages 11 and 15, were imprisoned by the United States government during World War II because of racist suspicions against their community. As a result, my parents, both consciously and unconsciously, raised me to assimilate into a white middle class identity. Growing up in a white suburb of Chicago, when someone said, “I think of you, David, just like a white person,” that was what I wanted to be. So I grew up studying and emulating white culture, white identity and white people. I know how white people think and view themselves because that is what I wanted to be — a white person.

Only in my late 20s, after reading African American authors, did I finally admit to myself I was never going to be white; moreover, these Black authors provided a language and a set of concepts that served as tools to investigate my Japanese American identity. I began to develop friendships with other people of color, particularly writers and artists, and I began teaching at organizations with students of color. So in many ways, in the second half of my life, I’ve been studying and developing relationships with Black culture, Black history and the Black community in a very conscious way, and I’ve been aided in that by key friendships with Black writers, artists, and theorists like the novelist Alexs Pate and a key proponent of the school of Afropessimism, Frank Wilderson.

You discuss fictional and historical examples of white supremacy in your book. Can you expand on how specifically fictional examples of racism fuel and protect the ideals that support white supremacy? How are these racial narratives different when presented by Black fiction writers and filmmakers?

Steven Spielberg and two white screenwriters created the film Amistad. In the initial scene, the Africans speak without subtitles — thus, unintelligible to American audiences — and after breaking their chains in the hold of a ship, they proceed to kill the white Spanish sailors. So the audience cannot understand them, does not know why they are in chains (they could be prisoners), and their first act is violence against white men. As the film progresses, it focuses on the quest of the young white lawyer, Roger Baldwin, to enlist John Quincy Adams to help in the trial which will determine whether the Africans are slaves or free men.

My friend, the African American novelist Alexs Pate, was hired to write the novelization of the film script, and intuitively he did not want to start with this scene. And so, unlike the film script, whose main viewpoint is that of Roger Baldwin and John Quincy Adams, Pate starts the novel within Cinque’s consciousness. Cinque is sleeping in his village next to his wife and child; he is restless and goes out and ends up killing a lion which is attacking his village. He is not unintelligible; he is a man with a family, a people, a culture; his consciousness is available to the reader; and finally his violence is clearly and unambiguously heroic. Just as importantly, his Blackness is not even a concept or, to use Dubois’ famous question, a problem. There is no Whiteness, and his status as a free man is not dependent upon the judgment and rule of white people.

Thus, the novelization written by an African American novelist differs markedly from the film, both in its ontology (categories of race) and its epistemology (whose knowledge and viewpoint centers the narrative). Pate uses all the lines from the script — that was his charge — but instead of a film about white saviors, he creates an African American film with an African hero whose goal is to return home to his wife and family.

You point out that white authors do not generally identify the race of their white characters and BIPOC writers do. What is the significance of this?

In general BIPOC writers understand that they must somehow indicate the ethnic and racial identity of their characters and in order to properly contextualize and understand their characters, they must be able to read those characters racially. In contrast, if a white author introduces the couple David and Susan, absent any racial marker, those characters are presumed to be white.

Thus, white identity becomes the universal default; all characters of color are exceptions to the norm. Moreover, whiteness need not be identified, and the implied assumption is that a white character being white has nothing to do with their identity, the way they look at themselves or their life experience — which, frankly, is nonsense. Thus, the absence of any racial marker for white characters becomes a mainly unconscious denial of race in America; it also implicitly assumes that the reader of the text is white and will not think consciously about the racial identity of the white characters or the author. This is not an assumption either most writers or readers of color make when creating or interpreting a text, even a text by a white author about white characters.

Writers and readers of color, a la DuBois’s double consciousness, know they must think about how white people think and how people of color think, whereas white consciousness can ignore the judgment and thinking of people of color or our ability to interpret and judge a text.

What does James Baldwin teach BIPOC about how to deal with America’s racism?

When Baldwin was in his teens and first ventured out of the all-Black community of Harlem, he was taken aback by the racism he experienced. After being refused service in a white New Jersey restaurant, he created a scene which ended with him being pursued by whites out of the restaurant. In his famous essay, Notes of a Native Son, he realizes that his father’s bitterness and rage concerning race also resides in his own psyche, and that if he doesn’t deal with that, he could end up killing someone or getting himself killed or killing himself.

Later, through his work as a journalist in the South during the Civil Rights era, he comes to realize the fortitude, resilience and spiritual strength of Southern Blacks in the face of the monstrous racism there, and how this strength resides not only in those activists, but in ordinary Black people who have continued to survive and build their own culture and institutions despite centuries of racism. At the same time, as Baldwin the writer and gay man encounters more of the white world, he realizes how deluded white people are not just about their racism but the false myths and stories through which white identity is created and maintained. He sees that white people are weaker and more morally bankrupt than they themselves can admit. As he says in that famous remark, he cannot be hurt by the N-word because the N-word says nothing about him or Black people but it says a lot about the people who created that word and use it to formulate their own sense of themselves and identity. In other words, he gives less and less room in his psyche to the ways white people see him; he makes Whiteness smaller in his own mind.

Tell us about Alexs Pate’s The Innocent Classroom and your involvement with the program.

I’ve been friends with the African American novelist Alexs Pate for 30 years. Back in the 1990’s we co-created a performance piece based on the events surrounding the video of the Rodney King beating by LA police. Partly inspired by pieces he wrote for that script, Pate eventually created a program to train K-12 teachers to improve their relationship with students of color.

In the program we asked educators to list the words American society uses to describe children of color and the list that results is an appalling array of negative stereotypes. The program understands that many BIPOC students feel branded and trapped by these negative racial stereotypes and never or rarely experience environments where their innocence — rather than their guilt — is assumed. And yet these are children; they should be regarded as innocent.

I served as Director of Training for the program and was the first trainer other than Pate to present the program to educators. Today, implemented in classrooms across the country, the Innocent Classroom has been shown to significantly improve both student behavior and academic achievement as well as teachers’ belief in, and relationship with, their students.

Why is the general view of white supremacy and the legacy of slavery overly simplistic and superficial? How, for instance, did the establishment, practice and justification of slavery structure white identity, as opposed to Black identity?

Racial disparities continue to exist in economics and employment, in the educational, justice and political system, in medicine and other fields, and as Baldwin has observed, these disparities are not an accident or a result of a few bad apples. They exist because white people have wanted them to exist and have structured power in this society so that these disparities can be maintained.

Such disparities exist because American society is still structured by the ways white people define Whiteness and Blackness, and the roots of that definition and grouping go back to slavery. From 1619 on, white identity was always formulated and viewed in contrast to Black identity. Historian David Eltis argues that it would have been more economically feasible to enslave whites from European poor houses and prisons, but Afropessmist Frank Wilderson points out that this would have broken up Whiteness as a group identity and as a tool to oppress racial others. Whiteness became the definition of what it means to be a citizen, to have the rights of citizenship, to have the rights to own property and later to participate in our democracy. Blackness became the definition of what it means not to be a citizen, to lack those rights, which meant that violence could be done to the Black body without need of legal justification — a phenomena we still see in contemporary encounters between Black people and police.

Of course Black people had a very different definition of what it means to be white and what it means to be Black and they resisted the categorization of themselves inflicted upon them, and this resistance continues into the present.

What does your book say about the racial thinking and psychology of Thomas Jefferson?

Let’s say I’m introducing you to a man who is a brilliant writer and thinker, an inventor and a scientist, a creator and purveyor of the principles of equality, freedom and democracy, a man who helped found a democratic nation. You would think: This is a man to admire.

But what if I told you this man enslaved over 500 human beings? What if I told you this man was his era’s leading ideologist in support of chattel slavery, that he argued vehemently for the inferiority of the Black race? What if I told you this man begat children in an adulterous affair with one of his slaves, who had no right or ability to reject his advances? What if I told you that this mistress was one fourth Black and his children one eighth Black, so that his children by this mistress/sexual victim looked white and people remarked on their resemblance to his father? But this man kept his own children and his grandchildren enslaved because their mother was Black. You would have a totally different opinion of this man. You would think him evil, psychologically depraved, morally bankrupt. The least you would say is that this man is a racist.

White America is fine with the presentation of Jefferson in my first paragraph here. White America is not fine with Jefferson the slaveholder and ideologist for slavery. And yet we are talking about the same man. You cannot understand how the United States was created, nor what it has been and is now, without acknowledging and understanding the moral, psychological and political contradictions Jefferson embodied. White America does not want to remember Jefferson the slave holder and it is this repressed truth which still shapes not only our thinking about the past and the present (for it is the present which clings to this historical amnesia).

Many have argued that we should view Lincoln’s racism as a product of its times and should be viewed in the context of its times. What is wrong with that view?

Certainly we should view Lincoln’s racism in the context of his time. He was a great president, a great man, and in so many ways a moral leader of his time.

And yet, he was also a racist, and there are any number of his remarks we would today recognize as racist, including his telling the Black ministers who came to the White House that they would never be part of America and that there was no Black person equal to a white person. We need to acknowledge this truth, because his racism is a fact about the man and his time.

We should be able to hold two views of Lincoln at the same time. Because if you eliminate the judgment of Lincoln as a racist, you distort and deny the past; moreover, if you lower the moral bar in judging the past it becomes way easier to lower the moral bar in judging the racism of the present.

Just as importantly, when we talk about the moral climate of Lincoln’s time, whose morality are we referring to? It is clearly just the morality of the white people of his time – because those Black ministers were also part of Lincoln’s time, and they believed in their equality and right to be part of America. So in calling for a white historical relativism, the present white view of Lincoln’s time eliminates the judgements and consciousness of the Black people of his time; it says those Black people were not part of America — which again is a racist view which characterizes our present as much as it characterizes Lincoln’s time.

How have we underestimated the lasting effects and complexity of the Reconstruction period?

After the Civil War, after any seeming legal racial progress towards equality, the regressive white population began work to re-establish the racial norms of the previous era — only without using the vocabulary of the previous era. Yes, the Emancipation Proclamation or the 13th and 14th Amendments supposedly became the law of the land, but these laws did not change the hearts and minds of white Southerners, particularly former slaveowners. So their question was: How can we reconstitute the power and trappings of slavery without saying that’s what we’re doing?

The Reconstruction period remains particularly obscured in our telling of American history. If anything is told, such accounts tend to involve stories of white vigilante violence, of the KKK and white terror, which were certainly part of this era. But the era also involved complex legal, philosophical, cultural and historical work, from the laws of the Black Codes, which essentially allowed any white person to arrest a Black person who was not working which then led to hundreds of thousands of Blacks trapped in the slave labor of the prison system; similarly apprenticeships and forms of indentured servitude kept Black workers constantly in debt to the white landowners and thus stripped of their rights. Then there were all the efforts to prevent Blacks from voting, from outright terror to poll taxes and written tests and other forms of voter discrimination.

And all this was supported by legal efforts to decrease the public sphere where laws of equality could be enforced and increase the private sphere where they could not — including designating racial hatred and discrimination as not being an essential part of slavery and thus, still perfectly legal; other legal work involved pushing state’s rights over federal rights and other measures out of a political philosophy which sounds today much like that of the Republican party. Finally, there was the production of the narrative of the Lost Cause, which depicted slavery as a relatively harmless necessity and certainly denied it as a cause for the Civil War; instead the Lost Cause myth pictured state’s rights and Northern aggression as the real reasons for the war, and it portrayed Southerners as noble, valiant, brave, and heroic freedom fighters in a lost cause. By the time of say Birth of a Nation or Gone With the Wind, this blatantly false narrative of the Lost Cause had even infected the northern view of the Civil War and the South. Indeed, adopting this narrative became part of how the North eventually chose unity with fellow Southern whites over any real work towards Black racial equality.

When white South Africans wanted to institute racial segregation and white supremacy in a formalized way, they realized the white American South had already created such a system and had done their work for them. Reconstruction created the Jim Crow South and kept and still keeps Southern Blacks from having equal rights there. The crisis of the Jackson, Mississippi water system reflects the fact that most whites moved out of Jackson to avoid school integration, and thus, what happened with the water system there is simply the colored water fountain, 2.0.

What is white epistemology and Black epistemology? How do these complex terms relate to the present day race relations?

Feminists have argued that gender shapes and influences our conceptions of knowledge and the practices through which we attribute, acquire and justify what is proper knowledge. Similarly, race shapes what we regard as valid and invalid knowledge; it shapes how we come to know and think about the world; it shapes how and whom we designate as possessing the truth of the world, both of the past and the present. Or as Robin DiAngelo, author of White Fragility, puts it, “From whose subjectivity does the ideal of objectivity come?”

People of color understand that a basis of white identity is always this: Nothing people of

color say about whites or Whiteness can be the truth — valid knowledge — unless whites and Whiteness decree it. Ultimately, whites believe it is their right to decide not just the nature of their reality, but that of blacks and other people of color too. It is their white epistemology, their way of knowing the world, which must remain supreme. For it is a fundamental rule of white epistemology that the knowledge and stories of white America can never be legitimately challenged by Americans who are not white. You see this white epistemology at work everywhere — in our political and legal system, in culture, in the ways we tell our history.

Throughout our history, but certainly within slavery, the white Master believed he is the master and the Black Slave the inferior who must do what the Master says — on pain of death. Implicitly, in the white Master’s epistemology, Black knowledge hardly existed and was certainly inferior and subject to the Master’s judgment. Blacks understood the white Master viewed them like this, but they also understood they needed to hide their consciousness, their rebellious thoughts and actions, from the White Master. The Black Slave knew a truth the White Master could not admit — the Black Slave was a fully human as the Master. So the Black Slave, as DuBois implied, had a double-consciousness and had to understand how the White Master thinks of himself and the Black Slave and how the Black slave thinks about themselves and the White Master.

How would our country be different if we had a new national narrative that includes the stories and experiences and voices of all Americans, not just the white-dominated narratives we are taught in school or, up until very recently, in popular culture?

As the historian David Blight has observed, “Hypocrisy is a tool of racism.” If the ways we narrate and tell our racial history is distorted and actively omits or obscures certain truths, we cannot understand either the past or the present which emerged out of that past. Moreover the distorted and censored way we tell our history continues, and this then distorts the way we tell our narratives about the present. It’s easier to lie about the present if you lie about the past; it’s easier to lower the moral bar in the present if you lower it in the past.

Beyond this the truths embodied in the narratives and perspective of African Americans are part of our entire nation’s history. Our national history does not make sense without their story and perspective. Moreover, within the struggle for civil rights, Black America has always been on the right side of history, has always seen our racial mistakes and problems more clearly than white people. And yet, curiously and tellingly, there can be no contemporary Harriet Tubman or Sojourner Truth or Martin Luther King, Jr. But if white America actually understood the full complexity and truths of our history, it might be more able to say, “Hey, we got the race question wrong every time in our history and you Blacks were on the right side of history. So now we’re going to listen to you, we’re going to take your lead.”

Part of this would involve white Americans understanding that they are inheritors, as we all our, of the white slaveowners and the Black slaves; George Wallace and Martin Luther King, Jr. are both part of our legacy. While some declaim the diminishment of white unblemished heroes like Jefferson who owned slaves and Lincoln who was a racist, we should be able to see the truly heroic in the struggles of African Americans and other BIPOC Americans and make their contributions essential to the American story, which they are.

One more point: Conservative whites are now proclaiming that the teaching about race in our classrooms is harming white children, and we should ban even a book like the story of Ruby Bridges, the brave 8-year-old who desegregated a school in face of hostile white crowds insulting and spitting at her. Why couldn’t white children be inspired by this story? Moreover if African American children can hear about the history of race in America, why can’t white children? Are white children so much more fragile? Finally, these white conservatives are clearly not concerned that almost every Black parent in America must tell even their grade school children what might happen to them if they encounter the police and how to avoid that. Where’s the concern for the real harm actual stories of the justice system are doing to Black children?

Where do we go from here? How can readers take what they have learned through your work and put that to action on an individual level to confront our country’s racial problems?

Near the end of the book, I go over some changes white people need to make in their lives, from knowing more about the issues of race to changing and making more diverse their social life to entering activism. But these fairly concrete steps must be taken in concert with an internal journey.

I point out how white reactions to racism often follow the five steps in Helen Kubler-Ross’s five stages of grief: denial, anger, bargaining, grief, acceptance. From denial: “Racism is mostly a thing of a past…” or “…there’s no such thing as systemic racism….” or “whites are more discriminated against than minorities…” to anger: “Why are you being so difficult, why are you created problems when there aren’t any, the problem is your anger, why do you keep bringing this up” to bargaining: “well, it can’t be all that bad….it’s only a few bad apples….we just need to make a few reforms to policing” to grief: “I can’t believe it’s so bad, how do you BIPOC people take it, I feel so ashamed” and white tears to finally acceptance of the fact of racism in American life and society. This is a spiritual and psychological journey, not just a political one.

For BIPOC people, we must reject how whites define racism — focusing mainly on conscious and visible individual acts of racism and discrimination — and instead understand the systemic workings of racism, how acts of racist acts in our justice system or politics often disguise their true intent, how racial disparities are created by structural components such as legal protections for egregious police officers or the systemic pervasiveness of unconscious or implicit racial bias in a huge proportions of America.

For BIPOC people, there’s also the task of making Whiteness — that is white judgements, insults, discrimination — smaller, with far less room in our heads. Yes, we have to battle the systemic racism in our society, but we must work on not internalizing that racism and letting it judge ourselves. As I often say to you BIPOC, “Don’t give power to people who cannot see you.”

A former award-winning journalist with national exposure, Marissa now oversees the day-to-day operation of the Books Forward author branding and book marketing firm, along with our indie publishing support sister company Books Fluent.

Born and bred in Louisiana, currently living in New Orleans, she has lived and developed a strong base for our company and authors in Chicago and Nashville. Her journalism work has appeared in USA Today, National Geographic and other major publications. She is now interviewed by media on best practices for book marketing.