FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE:

Willa Goodfellow’s series of edgy, empathic, and comedic essays sheds light on

an often-misunderstood mood disorder

BEND, Oregon –– She was going to stab her doctor, but she wrote a book instead.

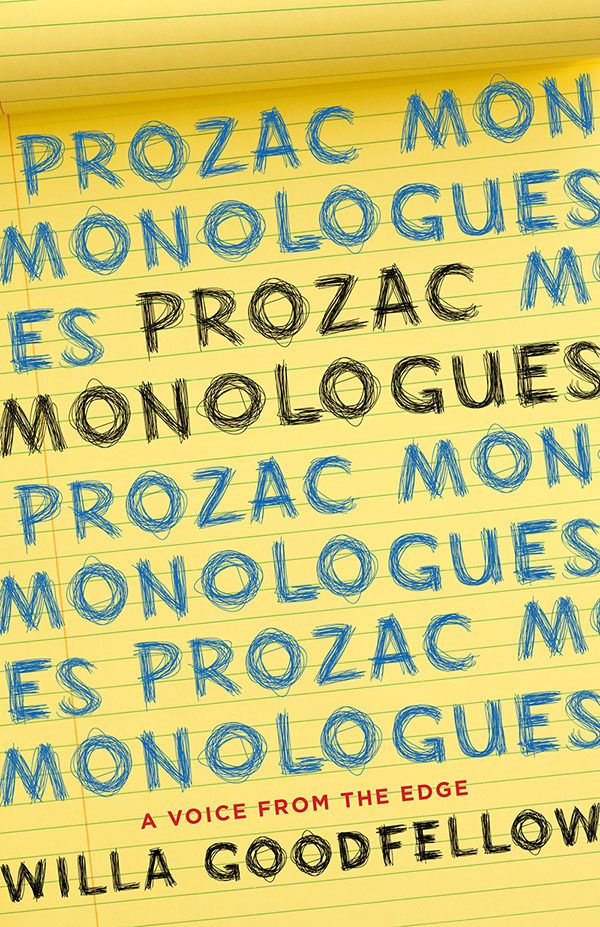

In her new book, “Prozac Monologues: A Voice from the Edge” (Aug. 25, 2020, She Writes Press) mental health journalist and Episcopal priest Willa Goodfellow shares her journey to recovery with transparent detail — from an antidepressant-induced hypomania that hijacked her Costa Rican vacation to the discovery that she had been misdiagnosed to learning how to manage life on the bipolar spectrum.

This raw, vulnerable collection of essays offers both a memoir and a self-help guide to others struggling with mental illness, including those on the bipolar spectrum who, like Goodfellow, are often initially diagnosed with depression.

Part of “Prozac Monologues” was penned in a hypomanic state and allows the reader to witness the inner workings of a racing and agitated mind. But Goodfellow also dedicates much of her work to describing in clear and accessible language the mechanics of a bipolar brain and how it is diagnosed, with the help of academic psychiatrists and current research findings.

Part of “Prozac Monologues” was penned in a hypomanic state and allows the reader to witness the inner workings of a racing and agitated mind. But Goodfellow also dedicates much of her work to describing in clear and accessible language the mechanics of a bipolar brain and how it is diagnosed, with the help of academic psychiatrists and current research findings.

“Prozac Monologues: A Voice from the Edge”

Willa Goodfellow | August 25, 2020 | She Writes Press

Paperback ISBN: | Price: $16.95

E-Book ISBN: | Price: $9.95

Self-help/Memoir

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Willa Goodfellow is the author of “Prozac Monologues: A Voice from the Edge” (Aug. 25, 2020, She Writes Press). Her early work with troubled teens as an Episcopal priest shaped an edgy perspective and preaching style. A bachelor’s degree from Reed College and a master’s from Yale gave her the intellectual chops to read and comprehend scientific research about mental illness—and her life mileage taught her to recognize and call out the bull.

Willa Goodfellow is the author of “Prozac Monologues: A Voice from the Edge” (Aug. 25, 2020, She Writes Press). Her early work with troubled teens as an Episcopal priest shaped an edgy perspective and preaching style. A bachelor’s degree from Reed College and a master’s from Yale gave her the intellectual chops to read and comprehend scientific research about mental illness—and her life mileage taught her to recognize and call out the bull.

So she set out to turn her own misbegotten sojourn in the land of antidepressants into a writing career. Her journalism has attracted the attention of leading psychiatrists who worked on the DSM-5. She is certified in Mental Health First Aid, graduated from NAMI’s Peer-to-Peer program, and has presented on mental health recovery at NAMI events and Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa.

Today she hikes, travels, plans seven-course dinner menus, works on her next writing project, “Bar Tales of Costa Rica,” and stirs up trouble. She lives with her wife, Helen, in Central Oregon, sometimes Costa Rica, and still misses her dog, Mazie. Connect with Willa online at:

https://willagoodfellow.com

https://www.facebook.com/WillaGoodfellowAuthor/

and on Twitter @WillaGoodfellow

In an interview, WILLA GOODFELLOW can discuss:

- What is bipolar disorder: not as simple as the movies make it

- Misdiagnosis and the misuse of antidepressants

- Understanding suicide and suicidal thoughts

- What recovery means for those with chronic or recurring mental illness

- Faith, religion, and mental illness

An Interview with WILLA GOODFELLOW

What motivated you to write this book? Did you experience any hesitation, and if so, how did you overcome this?

The opening scene of the book describes a traumatic experience. My brain was doing strange things. I didn’t know what was real. I was paranoid and scared. “Bizarre”,” the first monologue, was my attempt to deal with that experience by calling it a bizarre “thought” and getting some distance by turning it into a comedy routine. It wasn’t until 14 years later that I really faced it, rewrote the scene, being as specific as I could be, and for the first time took it to my therapist, and asked her to tell me clinically what had happened to me. I still hesitate to talk about it. But the more people have found out about the book, the clearer it has become to me that others really need to hear this story. So, I take a deep breath, and I tell it.

How is bipolar defined? Is it different than depression?

In the DSM, the book that doctors use to make diagnoses, bipolar is a mood disorder that shows up in two ways. Depression is the first way, with symptoms like sadness, loss of interest or pleasure, weight changes, sleep disturbance, agitation, fatigue, feeling worthless or guilty, difficulty concentrating or making decisions, and thinking about suicide. Bipolar is depression plus other experiences of mania or hypomania (mania-lite): intense feeling (whether up or irritable), inflated self-esteem, no need for sleep, flight of ideas, racing thoughts, distractibility, excess activity, and risky behavior. That’s how it’s diagnosed. But inside there is a lot more going on, a whole series of mis-timings and misalignments in a lot of different systems. Bottom line, bipolar is external and internal difficulty in maintaining balance.

Was there a defining moment that made you realize you were wrongly diagnosed?

I was on an airplane, talking with a doctor, a family physician about the first version of my book—the monologues from 2005. When he heard my story, he said when I get home, I should google the Mood Disorder Questionnaire. “Just remember MDQ,” he said. So I did. I added up my score, and it said I should talk with my psychiatrist about whether I have bipolar. Well I didn’t want that diagnosis. I didn’t tell anybody for another year or two, until I just was not getting better. Eventually I realized I wasn’t going to get better until I faced it, so I asked my psychiatrist to look at my diagnosis again, and told her about that time I wrote a book in a week while on vacation in Costa Rica.

Why is misdiagnosis so pervasive in mental illness?

Mental illness diagnoses are made on the basis of external signs and symptoms. They call them symptom silos. You get slotted into the silo that fits best on the day the diagnosis is made. But there’s overlap among diagnoses, variation in how each one shows up, variation over time, plus memory difficulties that affect what you report to the doctor. So when symptoms change, diagnoses change. They don’t use biomarkers in diagnosis, objective measures like blood tests, genetic testing, MRIs and fMRIs, which are pictures from inside the brain. People are doing more research into biomarkers these days, and I do believe they will make a difference.

What advice would you give others who think they may have also been misdiagnosed?

First, learn as much as you can about the bipolar spectrum. I’d recommend a book by Chris Aiken and James Phelps, Bipolar, Not So Much. Take the diagnostic instruments, the Mood Disorder Questionnaire and the Bipolar Spectrum Diagnostic Scale. Keep records of your own experience, what medications you are taking, what the side effects and your symptoms are. Use a mood chart daily, and track energy level, as well as mood. Get solid, concise information to take to your doctor, not just your vague memories or how you feel on one particular day.

How can people who think they may have been misdiagnosed advocate for themselves?

Now personally I hate this advice, but I take it from Aiken and Phelps. You need to have a good relationship with your doctor, and your doctor needs to feel in control. So, don’t walk in with your own self-diagnosis or overwhelm her/him with questions or challenges. Be precise, have your records in order so you don’t take a lot of time. Express appreciation for how hard you are to treat, or something the doc has done to help you. Ask wondering kinds of questions like “I wonder what this means, that I have these fluctuations of energy, or that I keep having these particular side effects to all the antidepressants we’ve tried.” I also found it helpful to bring my spouse with me to support me and to give information that I didn’t have the insight to give.

What is your relationship with antidepressants?

My personal relationship with antidepressants is that they are the wrong meds for my condition. So, they were dangerous to me. All medications have side effects. And often side effects fade over time, as your body and brain get used to this new chemical that’s been introduced into your system. But the really bad things that antidepressants are accused of, and that happened to me, things that got worse over time instead of better, are sometimes an indication that you’re taking the wrong med. You have to watch out particularly for agitation, irritability, insomnia, and increasing suicidal ideation. Those are things you have to tell your doctor about.

What do you think are the most common misconceptions about taking antidepressants?

One common misconception is that antidepressants are “happy” pills. You just pop the pill and you feel great again. That’s not how it works. Antidepressants don’t help you avoid your problems. Depression is like a coat of concrete that surrounds your thoughts, your emotions, your energy level. If antidepressants work for you, then they break up that concrete so you can move again and become yourself again. But then you have to do the work. You have to think through your situation, whatever that is, understand your feelings, all of them, make good decisions, and show up for your own life.

Similarly, what is your relationship with therapy?

I’m a big fan of therapy. I have had different therapists, each taking a different approach. What worked at one stage was less useful at another. I changed therapists once when we just got stuck. That experience actually helped me later. I learned how to speak up when things weren’t working with the next therapist and to renegotiate our work. Therapy has taught me a lot.

This book chronicles some of the darkest moments of your life, yet you pepper the pages with hope and even humor, something you wouldn’t expect to find in a memoir about mental illness. Why use humor?

Yeah, so many depression memoirs are just so. . . depressing. Now, when somebody isn’t willing to tell me the bad news, then I don’t trust them when they tell me they have good news. So, I try to tell it like it is. On the other hand, I don’t want to make myself miserable when I read my own book. Humor gives me just enough distance from my misery to let me face the ugly truth and then lets me lighten up, so I can get to a realistic hope.

Why do you feel it was important to consult with psychiatrists when writing this book, and what value do you think that it added?

I wanted a book that would not merely tell my story but also help others who might be on the bipolar spectrum to understand it. Bipolar is not simple, and we need all the information we can get to manage it. And to the extent that I am also addressing psychiatrists and psychologists on the topics of diagnosis and treatment, I want them to know that I’m not just shooting from the hip. I’m a really smart person, and I can read the research, but I didn’t go to medical school. So, I am indebted to a couple of research university psychiatrists, Ronald Pies and Jess Fiedorowicz, who helped me make sure that I got my facts right.

Is it true that part of your book was actually written in a hypomanic state?

Oh yes, I still have the scribbled yellow pad pages to prove it. I was driven, I was urgent, it was the most important thing I had ever done in my life, and I could not be diverted from it by something as mundane as. . . walking on the beach in Costa Rica! My wife was upset at the time that I wasn’t doing things with her. But I didn’t have any sense that there was anything wrong. And for years I didn’t understand how worried she had been. You know, even after writing a book about it, there’s a part of me that still thinks she was overreacting. That’s called lack of insight, and that, too, can be part of mania and hypomania.

You are very open about discussing your own struggles with suicidal thoughts. What do you think are the biggest misconceptions about people going through similar experiences?

The biggest misconception is that suicide is a choice, that suicidal people sit down, make a list of pros and cons, think it through, and decide. Suicide happens when pain exceeds resources for coping with pain, when people just reach the end of what they can do. The second biggest misconception is that there’s nothing you as a friend or family member can do, that only professionals can help. That’s just wrong. You can be a resource. Now, arguing with them doesn’t help. But anything that you do to relieve another person’s pain, any act of kindness helps to tip that balance away from pain and toward life.

You are an Episcopal priest. What difference did your faith make in your mental illness?

First, my religion, belonging to a church itself, gave me a foundational set of practices, a tradition of saints who had suffered in the past, and a wide group of friends that held me, so I knew that I was not alone, no matter what it felt like.

As far as my faith goes, I never believed that God is a fixer for good people, or that prayer works like the drive thru window at a fast food restaurant. Nevertheless, I was angry. I mean, this is happening to a priest? Seriously? –What can I say? The spiritual life is a series of discovering over and over that the God we believe in is not as big as the God Who Is.

How can we change the way we discuss mental health and be better advocates and allies?

The brain is part of the body. Like the rest of the body, it can malfunction. It can also recover. And if it is chronically ill, the illness can be managed. There’s nothing spooky or weird about that. We need people to push for a health care system that treats the whole body, neck up as well as neck down. It’s that simple.

Your book takes readers on a wild ride through your mental health journey. What is your life like now? How do you manage your mental health, and have you instituted any other effective lifestyle changes?

Mental health recovery works on four basic strategies: lifestyle, education and self-awareness, support, and medication. When you’re not in crisis, the most important is lifestyle. It’s been a long time since I was in crisis. But paying attention to my health is still a daily practice, especially keeping to a regular schedule. I stay on top of this, sleep, diet, exercise, therapy, self-monitoring, rescue meds as needed, so I can feel okay, so I can pursue my goals, so I can write, and speak, make dinner for friends, and enjoy my family, my beautiful home with its view of the magnificent Cascade Mountains, and my annual trip to Costa Rica. There are periods when I wobble, and there probably always will be. But my life is good. It is worth the effort.

A former award-winning journalist with national exposure, Marissa now oversees the day-to-day operation of the Books Forward author branding and book marketing firm, along with our indie publishing support sister company Books Fluent.

Born and bred in Louisiana, currently living in New Orleans, she has lived and developed a strong base for our company and authors in Chicago and Nashville. Her journalism work has appeared in USA Today, National Geographic and other major publications. She is now interviewed by media on best practices for book marketing.