Award-winning author Tessa Bridal was born and raised in Uruguay, leaving with her family when she was 20. Now, she returns to chronicle the stories of those who disappeared during the country’s political turmoil — following the stories of families, their loss and their resilience in her new book, “The Dark Side of Memory” (Oct. 26, 2021, Invisible Ink).

Award-winning author Tessa Bridal was born and raised in Uruguay, leaving with her family when she was 20. Now, she returns to chronicle the stories of those who disappeared during the country’s political turmoil — following the stories of families, their loss and their resilience in her new book, “The Dark Side of Memory” (Oct. 26, 2021, Invisible Ink).

“The Dark Side of Memory” is a gripping and incisive narrative of the multi-generational effect of the extremist military dictatorships in Uruguay and Argentina, as told to the author by families of the disappeared. Through her retelling, Bridal elevates the stories of the overlooked, voiceless and forgotten humans behind political turmoil.

As University of San Francisco Latin American Studies Program Director Roberto Gutiérrez Varea praises:

“Bridal offers us a poignant, clear-eyed view of the conflict, to best measure the viciousness of the military’s actions, and the courageous resilience of survivors and relatives who never gave up on their abducted kin. In the age of Black Lives Matter and the brutal detention of children by US Immigration Enforcement at the border, The Dark Side of Memory is a most caring and powerful cautionary tale as to the enduring, generational nature of trauma when political violence is unleashed on those most vulnerable.”

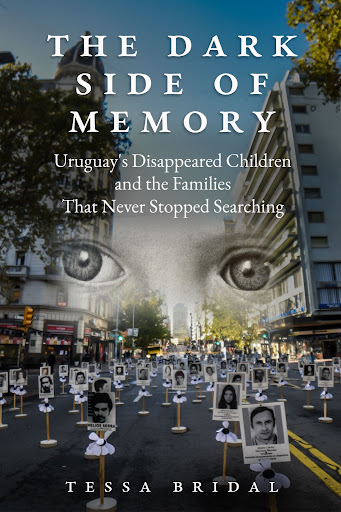

“The Dark Side of Memory: Uruguay’s Disappeared Children and the Families who Never Stopped Searching”

Tessa Bridal |Oct. 26, 2021 | Invisible Ink | Nonfiction

Paperback ISBN: 978-1-7369386-0-7 | Ebook ISBN: 978-1-7369386-1-4

About the Author

Tessa Bridal was born and raised in Uruguay, a third generation descendent of a resilient and courageous Irish woman who boarded a ship she had been informed was sailing for Boston. Once on the high seas she discovered that she was instead headed for Buenos Aires. (Her ancestor’s story is told in Bridal’s second novel River of Painted Birds.) Generations later, Bridal reached the shores her great-great-grandmother thought she was bound for. She worked in Washington DC saving to take a three- year acting and directing course at a London drama academy. She returned to the United States and settled in Minnesota, where she studied sign language and became Artistic Director of the Minnesota Theatre Institute of the Deaf. Her first novel The Tree of Red Stars won the Milkweed National Prize for Fiction and the Friends of American Writers annual award. Her work has been reviewed by the New York Times and praised by educators and historians. She is the recipient of the American Association of Museums (now the American Alliance of Museums) Educators Award for Excellence for her work in creating educational theatre programs that became the model not only for science and children’s museums, but for zoos and aquariums as well. She has worked at the Science Museum of Minnesota, the Indianapolis Children’s Museum, and the Monterey Bay Aquarium.

She is the proud mother of two daughters and grandmother of two boys (seven and five) with a promising future in wrestling, magical thinking, and experimental science.

Early Praise for “The Dark Side of Memory”

“A bright star in a constellation of creative nonfiction works about the violent conflicts of mid-late 20th century in Latin America, the book casts a profound human gaze on a most devastating personal and social tragedy. The Dark Side of Memory weaves its narrative slowly. It pulls you in until you are compelled to read on in spite of a growing sense of foreboding. You are entering the sacred grounds of deep loss and deaths foretold, only, you are doing so held by Bridal’s compassionate hand and beautifully evocative voice. It lifts the lesser known stories of Uruguayan victims of the dictatorships that plagued South America’s “southern cone” up to the altar of quotidian, anonymous heroism where they belong. Critically, it centers its narrative on the behind-the-scenes epic struggle to recover defenseless young children, some born in clandestine torture centers where their mothers were murdered by those who kept them as their own. In doing so, Bridal offers us a poignant, clear-eyed view of the conflict, to best measure the viciousness of the military’s actions, and the courageous resilience of survivors and relatives who never gave up on their abducted kin. In the age of Black Lives Matter and the brutal detention of children by US Immigration Enforcement at the border, The Dark Side of Memory is a most caring and powerful cautionary tale as to the enduring, generational nature of trauma when political violence is unleashed on those most vulnerable.”

— Roberto Gutiérrez Varea, Director, Latin American Studies Program, University of San Francisco

“Tessa Bridal’s The Dark Side of Memory has the immediacy of a novel. We travel alongside a group of indefatigable women: into the torture centers of the Argentine military junta; through their long bureaucratic battles to rescue the children who were stolen from them. This is a book about the way the violence of the past weighs on the future, shaping its possibilities. And it is also a book about how acknowledging that past—fighting against the seductions of forgetting—opens a less violent, more human future.”

— Toby Altman, National Endowment for the Arts 2021-2022 Fellow in Poetry

“This is a holy book—because it tells the truth, concretely and unflinchingly. In the midst of an inferno, The Dark Side of Memory points us to the lives of the mothers and grandmothers of Uruguay and Argentina who, out of great love for their children, refused to permit the perpetrators of devastation to have the final word. Tessa Bridal bears witness to the power of memory, truth-telling, and hope, and so also to the possibility of a just world. This is a tremendous work of love.”

— Ry O. Siggelkow, Director of Initiatives in Faith & Praxis, University of St. Thomas in St. Paul, MN

“These life stories, portrayed in all their vivid complexity by Tessa Bridal, honor the humanity of the many who were dehumanized by Latin America’s dirty wars. Her creative telling brings us as close as we can get to grasping the motivations behind the crime of enforced disappearance, and to feeling for ourselves its deep and lasting scars upon victims, families and societies.”

— Barbara Frey, Director, Human Rights Program, University of Minnesota

In an interview, Tessa Bridal can discuss:

- Her unwavering commitment to documenting the stories of the families featured in the “The Dark Side of Memory.”

- Understanding the impact of family separation. The similarity between the arrests carried out by the South American military and those of the U.S. immigration authorities, including the separation of infants and children from their parents. Argentina’s National Commission on the Disappeared reported that the effects of these experiences were traumatic, and “had a very serious effect on their personality. So serious that sometimes they died as a result.”

- The human cost of political dissent, and the generational damage of the disappearance of children.

- The courage and perseverance of women, and the role of family matriarchs in the search for missing kin. After decades searching for her missing daughter, son in law, and grandchild one of the heroic women featured in the book speaks of disappearance as “a permanent crime. It is a form of dying that doesn’t allow for death or life.”

- Elements of the Cold War not often brought to light, such as the participation of the United States in the Condor Plan, parts of which were resurrected after the 9/11 attacks. These include the passage of the Patriot Act and the Military Order, authorizing the creation of special military tribunals to try non-citizens, as well as secret detention sites where those arrested could be held indefinitely without legal representation.

An Interview with Tessa Bridal

Before we dive in, can you set the scene for us? Politically speaking, what was South America, specifically Uruguay and Argentina, like during the height of the Cold War era?

By the mid-1970s most of South America, including its two largest countries — Argentina and Brazil — were under repressive military dictatorships. Under these regimes it was not necessary to commit a crime in order to be arrested by the military. People lived in fear simply of being in the wrong place at the wrong time. Thousands emigrated to Argentina, the last hold out. It felt safer than other countries at the time, but with Juan Perón’s brief return to power, it soon became the most dangerous, and the number of the missing soared. Relatives who persisted in questioning the authorities risked joining the ranks of the disappeared.

Because many were taken to secret holding centers, the numbers of the disappeared are based on family reports. Argentina alone estimates 30,000 (out of a population of 23 million). Mass graves continue to be found. Uruguay estimates about 200 (out of a population of 3.5 million). Research reveals discrepancies between official and unofficial numbers. Unlike the Nazis in World War II, dictatorships were not known for their accuracy and kept few records (still coming to light or being produced with court orders).

A staggering number of children and adults went missing during these tragic times. What happened to them? How many survivors were there?

The number of Uruguayan children still missing and unaccounted for is between 17 and 20. An unknown number of the women arrested during the dictatorships were pregnant. Some were known by their relatives to be carrying a child, but there were cases where the woman herself didn’t know she was pregnant at the time of her arrest. Women associated in any way with guerrilla activities were under constant surveillance, and communication with relatives was difficult to impossible. Whether women gave birth while under arrest or at home, they and their babies were at risk. Many childless families were eager to “adopt” babies and children offered to them by the authorities running the secret detention centers, or taken from their homes at the time of their parents’ arrest. As more of these cases come to light, the numbers increase.

Why is this book important to you on a personal level?

Whenever I visited Uruguay I would hear about the disappeared, either in a news report or in conversations with relatives and friends. I began to research what led up to the arrests and disappearances and to meet with people who had been involved politically during these troubled times, including friends and family members. As I listened to the courageous and undaunted women who searched for years and decades to locate their children and grandchildren, I began to record and write their stories.

Eventually, I met some of the disappeared children (now adults) themselves, and was inspired by their willingness and generosity. One of them felt strongly that books should be written and documentaries and films made about the disappeared but wondered if anyone will be interested in children they have never met. I assured him that I would do my best to ensure that they are.

How did you connect with the families you profiled in your book, and how did you approach documenting their stories? Were any of the people you interviewed hesitant to share their experiences?

A friend who had been imprisoned and had a child born in prison in Uruguay introduced me to the organization Families of the Detained-Disappeared. They gave me the names of people willing to talk about their experiences. In all cases, I asked for permission to record the interviews and to take photographs. I encountered no reluctance to share their experiences. A certain initial reserve, yes. But that is very typical of Uruguayans, who are warm and welcoming, but don’t open up as readily as I have found people tend to do in the United States.

As someone who grew up in Uruguay and later left the country, did hearing these stories change your perspective and the lens through which you viewed political turmoil in Latin America?

Hearing the stories of the disappeared changed not only how I looked at Latin American politics, but how I looked at U.S. politics. I realized that I had not examined as many perspectives of either one as necessary for writing this book. I was not interested in judging and condemning, but in trying to understand how the events I was researching had come to pass. Where and how had things gone so wrong? I do not pretend to have arrived at all the answers, but from that time to this I have had an opportunity to study war and politics, their complexities, and the price children pay for our failure to learn from past mistakes.

Can you tell us more about the importance of family matriarchs and women in searching for the missing?

It is impossible for me to say with any certainty why it was primarily the mothers and grandmothers of the disappeared who never gave up and who put their own lives at risk to find their children and grandchildren. Both the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo in Argentina and the Uruguayan Madres y familiares de uruguayos detenidos desaparecidos (Mothers and Families of Detained Disappeared Uruguayans) were founded and are run by women.

In both countries women are exceptionally independent and in the eyes of some undaunted, aggressive fighters. Laws provide equal and free education for all sexes, women are proud professionals in many fields and have been for decades, and the strict separation of church and state (in Uruguay for instance, one is free to have as lavish a church ceremony as one wishes, but only marriages conducted by a judge are considered legal) all contribute to women’s empowerment and equality with men.

Why more men were not at the forefront of the struggle to find their families is worth its own book. Machismo is alive and well, but I believe that there endures an underlying feeling on the part of men that the home and children are still a woman’s purview. In these areas, the men support, but the women lead.

The title of your book, “The Dark Side of Memory,” has a beautifully somber and mysterious tone. What does it mean?

This is a quote from one of the women featured in the book. She used it to describe her granddaughter Mariana’s reluctance to accept her biological family: the dark side of her memories, the painful ones. Mariana’s biological parents have never been found, and the father in the family that illegally adopted her is currently in prison for his part in the disappearance of Uruguayan refugees in Argentina.

How do you think the experiences shared in your book parallel the experiences of families currently dealing with separation, especially at the U.S.-Mexico border?

The circumstances surrounding the issue are different. The consequences are not. The enforced separation of children from their families has long-term consequences for both parents and children.

What was the Condor Plan?

Wikipedia tells us that the Condor Plan or Operation Condor was a United States-backed campaign of political repression and state terror involving intelligence operations and assassination of opponents. This was officially and formally implemented in November 1975 by the right-wing dictatorships of the Southern Cone of South America.

Has voter suppression been an issue in Uruguay?

There is one instance of it in this book. A referendum on whether or not to revoke the amnesty granted to the military for crimes committed during the dictatorship. It called for 525,000 signatures; 595,000 people put their names to the petition. The recount and verification of signatures took a year. By invalidating signatures where there was the slightest discrepancy, the electoral commission brought the number below the required level. In violation of their right to confidentiality, the names and addresses of those whose signatures came under scrutiny were published, and they were invited to re-sign during a three day period at sites that remained open only during working hours. The revocation failed. The Mental Health and Human Rights Institute of Latin America believed that “the community administered its own punishment: forgetting. But amnesty does not bring about amnesia.”

How did Uruguay change once democracy returned?

The fact that marches and demonstrations in Uruguay are still held demanding government action on the conduct of the military, speaks volumes. Every 20th of May the Marcha del silencio (the March of Silence) takes place in Uruguay’s capital, Montevideo. Not only do the families of those still on the list of the disappeared march, holding placards with their loved ones names and photos, but they are joined by thousands of citizens in increasing numbers each year. It has taken decades to bring to justice a few of the military involved in the crimes of torture, kidnapping, and disappearance. Most Uruguayans would agree that the vast majority has so far got away with their criminal activities.

Praise for “The Tree of Red Stars”

“Tessa Bridal brings a fresh voice to Latin American literature in her first novel, “The Tree of Red Stars.” Bridal, who was born and raised in Uruguay, uses her book to present a harrowing account of that country’s takeover by a military dictatorship, a regime that violently demolished one of Latin America’s oldest democracies. As the story leads up to these dramatic events, Bridal describes life in Montevideo through the eyes of Magda, a young woman from an upper-middle-class family who has lived a sheltered and secure existence – until the growing political unrest threatens to erupt even within her own wealthy neighborhood. And when Magda’s friends and their families are endangered, she is forced to make use of her privileges in ways that will also be hazardous to herself. Bridal’s narrative concentrates on a matter-of-fact rendering of Magda’s transformation into a revolutionary, dispelling stereotypical notions about the relationship between social class and volatile political activism. Magda’s association with the socialist Tupamaro guerrillas stems less from entrenched political beliefs than from her loyalty to her friends and her love for the country in which she has spent her childhood. As “The Tree of Red Stars” proceeds, Bridal recounts Magda’s perilous activities with a chillingly understated sense of inevitability.” — The New York Times Book Review

“…Set in 1960’s Uruguay, Tessa Bridal’s first novel – winner of this year’s (1997) Milkweed National Fiction Prize – is a skillful, utterly engrossing portrait of a social conscience awakening against fervent and often furtive friendships, personal and political loyalty, filial defiance and impossible love. … The Tree of Red Stars is an unpredictable and exquisite story.” — Time Out New York Review

“A moving and fictional account of events that must be remembered.” — Booklist

“A luminously written debut novel, winner of the 1997 Milkweed Prize for Fiction, about love and ideals under siege in 1960’s Uruguay. … Love and the past beautifully evoked in a faraway place…” — Kirkus Reviews

“…Bridal writes with power and compassion…this novel is recommended for all libraries.” — Choice

“…the straightforward plot effectively captures the terror or modern despotism as well as the hope necessary to overcome it. Recommended for all libraries. The book was also selected for the 1998 Teen List by the New York Public Library and was one of 6 books chosen by The Independent Reader as one of the year’s “most recommended” titles.” — Library Journal

A former award-winning journalist with national exposure, Marissa now oversees the day-to-day operation of the Books Forward author branding and book marketing firm, along with our indie publishing support sister company Books Fluent.

Born and bred in Louisiana, currently living in New Orleans, she has lived and developed a strong base for our company and authors in Chicago and Nashville. Her journalism work has appeared in USA Today, National Geographic and other major publications. She is now interviewed by media on best practices for book marketing.