Joni Sensel’s true story of numinous experiences gives meaning to the unknown

Joni Sensel’s true story of numinous experiences gives meaning to the unknown

SEATTLE, Washington – From nearly the start of their fairy-tale romance, Joni Sensel knew she would lose the man whose love changed her life. A dark premonition had warned her. Though she kept this secret in their short time together, upon his death she’s compelled to share it in a letter addressed to his spirit.

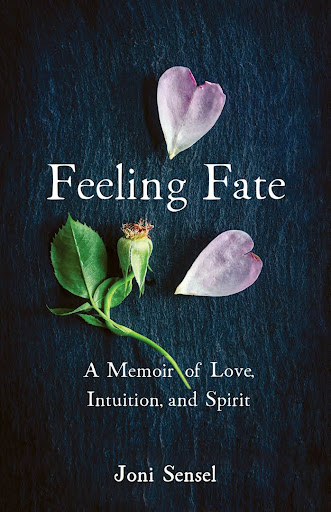

In “Feeling Fate” (She Writes Press, April 26, 2022) Sensel defends the insights of the heart regarding love, intuition, hints of an afterlife, and other experiences that defy logical explanation.

A grief memoir with a paranormal twist, “Feeling Fate” explores how Sensel’s dark intuition magnified her love and gratitude for her partner before her premonition came true. Torn between faith and skepticism after the loss, Sensel is nearly undone by her grief—until further uncanny experiences help her defeat despair and find meaning in the irrational insights of the heart.

An intimate and soulful read with some playful humor, Sensel proves that sharing our spiritual and intuitive experiences can lead us to a more fulfilling, joyous understanding of life and love.

“Feeling Fate: A Memoir of Love, Intuition and Spirit”

Joni Sensel | April 26, 2022 | She Writes Press | Memoir

Paperback | 978-1647423391 | $16.95

About the author…

JONI SENSEL is the author of more than a dozen nonfiction titles for adults, five novels for young readers from Macmillan imprints, and two picture books. Her fiction titles include a Junior Library Guild selection, a Center for Children’s Books “Best Book,” a Henry Bergh Honor title, and a finalist for several other awards. Her nonfiction titles have given her a dangerous level of knowledge about industries as diverse as public power, wood products, kidney disease, Lean manufacturing, recycling, and healthcare. She balances this education by avoiding any knowledge whatsoever about professional wrestling, hit TV shows, or K-pop.

Sensel holds an MFA in Writing from Vermont College of Fine Arts (2015). She previously served for four years as a co-regional advisor for one of the nation’s largest chapters of the Society of Children’s Books Writers & Illustrators (SCBWI), with more than 700 members. More recently she served as this chapter’s Creativity Liaison, among other volunteer roles.

Over the past 18 years, Sensel has taught dozens of writing workshops and seminars in locations from Alaska to Amsterdam for local, regional, and international organizations. A certified Grief Educator and First Aid Arts responder, she’s recently focused her courses and online workshops on creativity and spirituality topics.

Sensel’s adventures have taken her to the corners of 15 countries, the heights of the Cascade Mountains, the length of an Irish marathon, and the depths of love. She lives at the knees of Mt. Rainier in Washington State with a puppy whose presence in her life reflected afterlife influence.

In an interview, Joni Sensel can discuss:

- What a numinous experience is, and why these experiences are often dismissed or treated with suspicion

- Why she chose to share the story of her premonition

- Why we should consider strengthening our intuition, and how we can do this

- How creativity can soothe grief

- How conversations surrounding death and pain will help us as a society

Joni Sensel

What is a numinous experience, and how common are they?

It’s a perception or event with emotional impact that seems outside of normal experience, provoking mystical or spiritual feelings or a sense of a larger reality we don’t understand. They’re often called “woo-woo” experiences because they’re hard to explain rationally—and Western culture prioritizes reason over all other human experience or perception.

But they’re more common than you might think—surveys suggest that half of Americans have had such an experience. Most people simply hesitate to talk about them because we’ve been trained to be suspicious of anything we can’t count or test in a lab—and to make fun of anything that smacks of the paranormal.

What’s the earliest experience you had that suggested there’s more to the world than it seems?

First, I became aware of death at an unusually young age, since I was involved in events that led to the death of my baby sister when I was three. The aftermath of her loss, in which we didn’t really speak of her but I knew she’d once existed, taught me that what can be seen or acknowledged does not necessarily reflect the whole story.

Then, when I was about four years old, I spent a year living in my grandmother’s house, which was haunted with some kind of malicious energy that was invisible but quite tangible. I had to regularly navigate this unhappy presence, which I called the stair ghost. Only once I was older did I discover that my mom and several other relatives acknowledged its reality—including an uncle who was a science teacher, so not exactly a whimsical sort. That “ghost” was a tangible force well into my adulthood, and whatever it was—energy or spirit or something else altogether—it utterly convinced me that dismissing such phenomena as imagination simply because we can’t prove or quantify it is naïve, if not willful denial.

Why are numinous experiences and intuition often treated with raised eyebrows?

Because with the ascendance of rationalism in the last few hundred years, science has tended to respond to things it can’t readily quantify or test by denying they exist at all—even though science has very little of use to say about the things most people agree make life worth living, including love, a sense of awe, and consciousness itself.

But we’re not good at admitting there are things we not only don’t know, but perhaps can’t know. It makes us feel uncomfortably out of control. This reluctance has been exacerbated by our patriarchal society, which has frequently denigrated the realm of emotions and nonrational sensations as the realm of women, and therefore less valuable than “male” rationalism. Finally, there’s a vein of intellectualism that is distinctly anti-religion, and numinous experiences often carry spiritual implications or content. As a result of these attitudes, we’re suspicious of mystical or other experiences that can’t be analyzed, and it’s emotionally easier to dismiss anyone who reports such experiences as childish, deluded, or mentally ill.

And nobody wants to be considered foolish. It’s easier to say nothing at all, which only reinforces the impression that only kooks or people with overactive imaginations have such experiences.

What can others do to sharpen their intuition?

I think the most important steps are to acknowledge that it’s real, that the voice of your heart or soul is worth paying attention to, and to turn down the noise of our busy external lives so you can actually hear the quieter impulses that rise from deeper within. There are specific techniques that can help, from taking part in rhythmic physical activities to meditating or keeping a dream journal, but none of those will matter if you don’t have an open mind about the validity of intuition. I like to think of the subconscious, and with it, intuition, as like a dog—the more positive attention you give it, the more it will offer the behavior you reward.

What do you hope readers will take away from reading about your experiences?

I’d really like this book to prompt readers who’ve had their own spiritual or numinous experiences to reflect on them and feel encouraged to share without shame or hesitation. If they haven’t ever experienced any sense of the mystical, I hope my examples might open their minds to the possibility. I also hope readers who have struggled mightily with grief or depression, like I have, will find community and feel less alone or “wrong.” And finally, if there are any readers who don’t already believe true love exists or might still be out there for them, no matter their age, I hope my example in this book will convince them.

A former award-winning journalist with national exposure, Marissa now oversees the day-to-day operation of the Books Forward author branding and book marketing firm, along with our indie publishing support sister company Books Fluent.

Born and bred in Louisiana, currently living in New Orleans, she has lived and developed a strong base for our company and authors in Chicago and Nashville. Her journalism work has appeared in USA Today, National Geographic and other major publications. She is now interviewed by media on best practices for book marketing.