Pirates, prophecies, love, and survival – True stories offer a new look at life in Post-Imperial and Revolutionary China, as experienced by four generations of women

Qin Sun Stubis grew up in the squalor of a Shanghai shantytown during the Great Chinese Famine, her once-prestigious family shunned as political pariahs and forced to endure chronic poverty, torture, treacherous political shifts, and even an assassination attempt. But their nights came alive with stories of the family’s incredible history: colorful tales of pirates, prophecies, fortunes won and lost, glorious lives and gruesome deaths. Based on actual experiences and family lore from the Post-Imperial to Post-Cultural Revolution eras, Qin – a longtime newspaper columnist exploring the similarities and differences between East and West – has united these stories in a gorgeously-written and gripping nonfiction narrative, “Once Our Lives: Life, Death and Love in the Middle Kingdom” (June 1, 2023, Guernica Editions), uncovering one of the most fascinating yet largely overlooked portions of Chinese history, as told by those who lived it.

Qin Sun Stubis grew up in the squalor of a Shanghai shantytown during the Great Chinese Famine, her once-prestigious family shunned as political pariahs and forced to endure chronic poverty, torture, treacherous political shifts, and even an assassination attempt. But their nights came alive with stories of the family’s incredible history: colorful tales of pirates, prophecies, fortunes won and lost, glorious lives and gruesome deaths. Based on actual experiences and family lore from the Post-Imperial to Post-Cultural Revolution eras, Qin – a longtime newspaper columnist exploring the similarities and differences between East and West – has united these stories in a gorgeously-written and gripping nonfiction narrative, “Once Our Lives: Life, Death and Love in the Middle Kingdom” (June 1, 2023, Guernica Editions), uncovering one of the most fascinating yet largely overlooked portions of Chinese history, as told by those who lived it.

“Once Our Lives” is the remarkable true story of four generations of Chinese women and how their lives were threatened by powerful and cruel ancient traditions, historic upheavals, gender oppression, and a man whose fate – cursed by a superstitious prophecy that appears to come true – dramatically altered their destinies. The book takes the reader on an exotic journey filled with luxurious banquets, lost jewels, babies sold in opium dens, kidnappings at sea, and a desperate flight from death in the desert – seen through the eyes of a man for whom the truth would spell disaster and a lonely, beautiful girl with three identities.

This poignant epic offers an intimate look into the extraordinary lives of ordinary people living behind China’s greatest historical headlines – with a narrative so incredible that had it been written as fiction, people might not believe it.

Once Our Lives: Life, Death, and Love in the Middle Kingdom

Qin Sun Stubis | June 1, 2023 | Guernica Editions | Creative Nonfiction, Historical Memoir

Paperback | ISBN: 978-1-77183-796-5 | $21.95 (U.S.) / $25 (Canadian)

About the Author

QIN SUN STUBIS was born in the squalor of a Shanghai shantytown during the Great Chinese Famine. Growing up during the Cultural Revolution, she quickly learned that words could thrill – and even kill. She saw her defiantly honest father imprisoned and tortured for using the wrong words. Shunned as political pariahs, Qin and her family sustained themselves with books and stories of adventure and past glory. With the help of a borrowed radio, an eccentric British teacher, and a fortuitous assignment as a library assistant, Qin discovered and fell in love with Western literature, committing to memory the strange but beautiful sounds of Keats, Wordsworth, and Lincoln.

QIN SUN STUBIS was born in the squalor of a Shanghai shantytown during the Great Chinese Famine. Growing up during the Cultural Revolution, she quickly learned that words could thrill – and even kill. She saw her defiantly honest father imprisoned and tortured for using the wrong words. Shunned as political pariahs, Qin and her family sustained themselves with books and stories of adventure and past glory. With the help of a borrowed radio, an eccentric British teacher, and a fortuitous assignment as a library assistant, Qin discovered and fell in love with Western literature, committing to memory the strange but beautiful sounds of Keats, Wordsworth, and Lincoln.

But it was in bed late each night, after scouring local parks for enough firewood to cook the family’s meal of rice, that Qin and her three small sisters heard the dramatic stories that make up this book. The four girls listened to their mother, an aspiring actress in the early days of Asian cinema, recount colorful tales of pirates, prophecies, fortunes won and lost, babies sold in opium dens, glorious lives and gruesome deaths. Based on actual experiences and family lore from the Post-Imperial to Post-Cultural Revolution eras, these stories represent a wealth of colorful but largely overlooked Chinese history.

Eventually, through sheer grit and perseverance, Qin won admission to the famed Shanghai Institute of Foreign Languages and graduated with a bachelor’s degree in English and English Literature. With the help of family, friends, and a powerful U.S. Senator, Qin was granted a visa to study abroad. She arrived in America with two suitcases and not much more. After winning several scholarships, she graduated with a master’s degree and a profound love for her new adoptive country.

For the past 15 years, Qin has been a newspaper columnist and writes poems, essays, short stories, and original Chinese tall tales inspired by traditional Asian themes. Her writing is inflected with both Eastern and Western flavors in ways that transcend geography to touch hearts and reveal universal truths. Learn more: www.QinSunStubis.com.

Follow Qin Sun Stubis on social media:

Facebook: www.facebook.com/qinsun.stubis Instagram: @QinStubis

In an interview, Qin Sun Stubis can discuss:

- How living in China during the Great Chinese Famine affected her and her family physically, emotionally, and financially

- The unlikely means by which Qin got her education and changed her life while experiencing poverty (including banned books, a borrowed radio, and an eccentric British teacher)

- The most exciting stories from her new book (and there are plenty to choose from!), such as stories about lost jewels, babies sold in opium dens, kidnappings by pirates, and a desperate flight from death in the desert

- A reflection on how China has changed over time, and what can be learned about its history – plus what is most overlooked / misunderstood about her home country

- Feminism and cultural gender oppression, as well as the remarkable power of women to stand up to world-shaking challenges and overcome them

- The rising tide of anti-Asian sentiment and how the stories in this book may help build people’s understanding of an ancient culture and emerging superpower

- How the concepts of fate and superstition have shaped her life

- How she immigrated to America and embarked on a career as a writer and newspaper columnist despite the odds

An Interview with

Qin Sun Stubis

“Once Our Lives” is bookended by a mysterious, ancient superstition that seems to change the fates of two families over several generations, and, strangely enough, seems to come true. Can you briefly tell the story of how this all began?

When my grandmother was 19 years old and pregnant with her first child (my father), she found a beggar at her door. She fed him every day for seven days, but his visits stopped the day my father was born. One day, as my grandmother nursed her baby and pondered the beggar’s visits, she suddenly saw his eyes in her child and realized that the beggar had been all along a “wandering soul” in search of a host and he was now inside my father! Although my father was born into a prosperous family, my grandmother knew the beggar’s dark fate would take over his life.

How much of what shaped your family’s destiny do you think was due to real-life circumstances, and how much was due to cultural mores, superstitions, or just peoples’ belief itself in superstitions?

Here in the west, people often use the phrase “in the wrong place at the wrong time” for unfortunate events and “in the right place at the right time” for lucky occurrences. We cannot choose when and where we are born, but time and place do affect significantly how our lives unfold. My family went through extraordinary times in modern Chinese history, including wars, famine, natural disasters, and revolution, so it is hard to attribute our lives’ struggles to any one specific cause. However, it was definitely my grandmother’s sincere belief that my father was doomed before he was even born. Whether or not you believe in “fate,” people’s beliefs and expectations often do end up shaping their lives. Certainly, in the case of women, age-old cultural barriers, taboos and discrimination were strong enough to significantly affect their fortunes. And while people in the same historical period in China all went through what we went through, somehow, for my family, whatever could go wrong went wrong. My father ran into problem after problem and was even arrested and imprisoned twice, once for being for the Cultural Revolution, and once for being against it. It seemed that he simply could not win and that life was somehow against him. My grandmother attributed everything to his beggar’s fate.

How has China changed? And how has it stayed the same?

As a country, China has changed so much during the 50 years since it opened up. In the 1980s, I was an international tour and cultural guide in Shanghai and around the country for seven years. I knew Shanghai and some other major cities like my own fingers. Six years after I left for the United States, I went back and couldn’t recognize my own city. Every few years, I went back and it kept on changing. Skyscrapers shot up like bamboo shoots, old neighborhoods were leveled and gone, and the city skyline has been totally transformed and redefined again and again. China’s infrastructure is improving at lightning speed and, physically at least, the Chinese people’s way of life has been altered for the better.

But underneath the surface changes, I see the stubborn roots of our old cultural traditions, rituals, and even superstitions, some of which are embedded in the bedrock of 5,000 years of Chinese history and couldn’t be uprooted even by the gigantic tide of the Cultural Revolution. During holidays, family gatherings, and in everyday life, they are still being quietly observed and unconsciously passed down from generation to generation. In spite of their own denials and decades of official efforts to erase them, young people are weaving these rituals, beliefs and traditions into the fabric of their lives.

Let’s talk about the role of women in China. You write that women were sometimes seen as mere vessels for bearing sons and their status rose or fell depending on whether they delivered a boy or girl. In fact, women were sometimes not even referred to by their names, but as “the child’s mother” or “so-and-so’s daughter-in-law.” Was this your mother’s experience?

For many centuries before the founding of the People’s Republic of China, women had been the vessels for bearing sons and carrying on the family line for their husbands’ families. Their social status depended on having boys. After the founding of the People’s Republic of China, Chairman Mao himself proclaimed that men and women were equal, and that women were capable of “holding up half the sky.” And yet, the fate of Chinese women seemed to have changed less than you might expect. Women like my mother still suffered greatly all their lives for not being able to bear sons. As girls without brothers, we were looked down upon by our relatives. When the Sun family had any celebration, my mother and the four of us little girls were never invited. We were never in any of the Sun family photos. Our birthdays were ignored and our existences considered trivial. At the time when our family lived in the shantytown in the late 1950s and mid-1960s, my mother was often only called the “Sun family’s daughter-in-law.” Few even knew what her real name was. She was just part of the Sun family.

The only time my grandmother gave me a present was the night before I left for America. She arrived at our house with my grandfather, pressed a roll of money in my palm and said, “Buy yourself something.” Luckily, the room was dark and she couldn’t see the rage in my eyes. I didn’t want her money. It was too late to repair our relationship. I suppressed my anger and tried hard not to say anything bad. The next day, I left the money at home and told my father to give it back to her before I boarded the plane.

How did the hardships you experienced growing up in China shape your character?

I would say my character and personality have been deeply molded by hardships and uncertainties. While growing up in such harsh conditions was difficult, it did temper and train me to be resilient and resourceful. When I was little, I often wished bad times would end, my family would have enough food to eat, my father hadn’t been taken away, and my sisters and I had enough warm clothes in the winter so we wouldn’t have frostbite all over our fingers and toes…but none of my wishes were ever answered. I had to confront some harsh new reality every day and find ways to make my life a bit more manageable. Yet, I always held onto the hope that tomorrow would be a better day: It would be warmer, we would have more food, and my father would be returned to us. And I learned that no one could take away my right to hope and wish. They were the only riches I had in life. It was my hopes and wishes that carried me all the way to a university in Shanghai and eventually across the ocean to the United States.

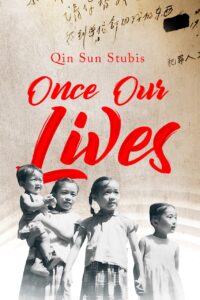

What is the story behind the cover design for “Once Our Lives?”

The central image in the book cover is a rare picture of the four Sun sisters – Wen, Ping, me and Min – shot in Jubilee Court, Shanghai around 1967 by a neighbor who was taking pictures of his own children. Having just a bit of extra film left in his camera, he called us over and asked us to line up for a photo. This was just how we looked that summer day, with pigtails made by our mother and clothes hand-sewn by her, as well. It was one of the only photos we have from our childhood because few people had cameras at the time, and we didn’t have the money to go to a photo studio. Very soon after that picture was taken, the first waves of the Cultural Revolution crashed into our lives. Our father was arrested and put into detention for speaking up about an unfair situation affecting the co-workers he represented as a union leader, and our neighbor never asked to take our picture again. I chose this picture because it captured a happy and hopeful moment for the four “worthless” Sun family daughters, the only treasures my parents ever had. At the top of the book cover are words from a postcard my father sent to us from his detention cell. Addressed to my older sister, Ping, my father’s fond signoff, “Your father,” was blacked out by an official censor, and the word “Criminal” was added beneath in someone else’s handwriting. Few postcards he wrote ever reached us, which were the only signs we knew that our father was still alive.

Why did you write this book? What do you hope readers will take away from your writing?

Since I was a child, I have always loved books. They gave me an escape when life became too hard, which was almost every day when I was growing up. But I never imagined myself writing a book, let alone one in English, which, after all, is not my mother tongue. After my parents passed away some 20 years ago, I missed them so much that I often spent long hours thinking about them and remembering the lives they had lived. The old stories my mother had told me over the years also came flooding back to me, bequeathing me a wealth of fantastical tales. I couldn’t believe how much my parents had lived through. I realized that if I didn’t write their stories down, an important part of history would be lost – along with a last chance for justice for my family. It was then that I decided to become the chronicler as well as defender of their lives. I wanted my children to learn about them. I wanted anyone interested in history and humanity to learn about them. My book is not just about Chinese history, because people from all parts of the world have also experienced wars, famines, and revolutions at one time or another. We all go through hard times and have to meet the challenges of our times. As my readers follow the footpath of our once-lived lives, I hope they will see the similarities, as well as the differences between our lives and theirs, better understand our common humanity, and be inspired to hold onto their own hopes and dreams as once we did.

Advance praise for “Once Our Lives”

“Stubis offers the reader a sweeping story, rich with detail…”

– Kirkus Reviews

“A moving account of family lore and life, Once Our Lives is paradoxically both heartrending and heartening – heartrending in its depiction of this family’s suffering and heartening in its depiction of the love that survives it all. I was riveted and moved.”

– Gish Jen, award-winning author of “Thank you, Mr. Nixon,” one of Oprah’s Favorite Books of 2022, The New Yorker’s Best Books of 2022, and NPR’s Books We Love

“This gripping memoir illuminates the full humanity of real people across four generations as they traverse the tectonics of modern China, buffeted between youthful idealism, political movements and cultural drag. A truly haunting tale of resilience, endurance and hope.”

– Helen Zia, acclaimed author of “Last Boat out of Shanghai: The Epic Story of the Chinese who Fled Mao’s Revolution”

“Qin Stubis combines oral traditions of mythologized family lore with the creative non-fiction writing of memoir. The reader experiences firsthand the vacillations of recent Chinese history.”

– Dr. Jennifer Rudolph, Professor, Asian History and International/Global Studies, WPI, and co-author of “The China Questions” books (Harvard University Press)

“A wonderful writer whose extraordinary ability and beautifully descriptive writing allow her to share her unusual experiences with readers in a uniquely powerful way. She is a writer whose generous, caring style has great appeal to a wide audience.”

– Diane Margolin, editor and publisher, the Santa Monica Star

“Qin Sun Stubis is notable for the warmth of her writing, the colorful originality of her work, and her ability to touch the hearts and minds of a wide variety of readers – a rare talent.“

– Christine Crosby, founder and editorial director, GRAND Magazine

A former award-winning journalist with national exposure, Marissa now oversees the day-to-day operation of the Books Forward author branding and book marketing firm, along with our indie publishing support sister company Books Fluent.

Born and bred in Louisiana, currently living in New Orleans, she has lived and developed a strong base for our company and authors in Chicago and Nashville. Her journalism work has appeared in USA Today, National Geographic and other major publications. She is now interviewed by media on best practices for book marketing.