DURHAM, NC – Stephen C. Pollock’s debut collection nods to the literary traditions of years past while simultaneously speaking to the present moment. Multilayered and musical, the poems in Pollock’s “Exits” (Windtree Press, June 29, 2023) have drawn comparisons to the work of Eavan Boland and Seamus Heaney. With bold imagery, attention to form, and a consistent throughline rooted in the theme of mortality, his collection responds to contemporary anxieties surrounding death and the universal search for meaning in life’s transience.

DURHAM, NC – Stephen C. Pollock’s debut collection nods to the literary traditions of years past while simultaneously speaking to the present moment. Multilayered and musical, the poems in Pollock’s “Exits” (Windtree Press, June 29, 2023) have drawn comparisons to the work of Eavan Boland and Seamus Heaney. With bold imagery, attention to form, and a consistent throughline rooted in the theme of mortality, his collection responds to contemporary anxieties surrounding death and the universal search for meaning in life’s transience.

From “Steve’s Balloons,” which was awarded the 2nd Place Prize for the 2020 Thomas H. McDill Award:

I saw then that balloons are not at all round

but are shaped like tears,

that a dream is not so much

that scrap of rubber on the ground

as the breath that once filled it.

“Exits”

Stephen C. Pollock | June 29, 2023 | Windtree Press | Poetry

Paperback | ISBN: 978-1-957638-68-3 | $12.95

Ebook | ISBN: 978-1-957638-67-6 | $3.95

Praise for “Exits” and Stephen C. Pollock…

“Full of wit, insight, and provocative imagery, Exits is a masterful collection by award-winning poet Stephen C. Pollock. Some are sonnets as artful as any by Shakespeare or Ben Jonson.”

—IndieReader, 5.0 stars ★★★★★

“A unique and diverse group of harmonious poems…producing the multilayered depth that distinguishes lasting poetry.”

—BookLife Reviews, EDITOR’S PICK

“Dedicated to the beauty and frailty of life, the poetry collection Exits exemplifies the musicality of language.”

—Camille-Yvette Welsch, Foreword Clarion Reviews

“Pollock’s poetry is brilliant. The exploration of form is thoroughly enjoyable and inspiring. Many of Pollock’s pieces are reminiscent of Irish poets like Eavan Boland and Seamus Heaney.”

—Kristiana Reed, Editor-in-Chief, Free Verse Revolution

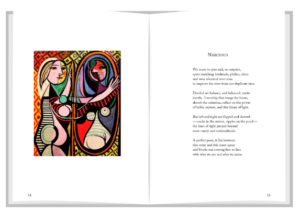

A look inside…

About the Author…

Stephen C. Pollock is a recipient of the Rolfe Humphries Poetry Prize and a former associate professor at Duke University. His poems have appeared in a wide variety of literary journals, including “Blue Unicorn,” “The Road Not Taken,” “Live Canon Anthology,” “Pinesong,” “Coffin Bell,” and “Buddhist Poetry Review.” “Exits” is his first book. To learn more, visit www.exitspoetry.net.

Stephen C. Pollock is a recipient of the Rolfe Humphries Poetry Prize and a former associate professor at Duke University. His poems have appeared in a wide variety of literary journals, including “Blue Unicorn,” “The Road Not Taken,” “Live Canon Anthology,” “Pinesong,” “Coffin Bell,” and “Buddhist Poetry Review.” “Exits” is his first book. To learn more, visit www.exitspoetry.net.

In an interview, Stephen C. Pollock can discuss:

- How he reconnected with his love for poetry after a 26-year hiatus

- His writing process, and how he uses formal elements in his work

- Why he paired the poems in this collection with visual art, and how the artworks represented were chosen

- Why the theme of mortality is woven through his collection, and what he’d like readers to take away from his work

An Interview with

Stephen C. Pollock

How did you get started writing poetry?

I began writing rhymed poems on shirt cardboard at age nine. “Yertle the Turtle” by Dr. Seuss was a strong influence. In my sophomore year of high school, my English teacher had his students maintain a poetry notebook for half the year. My notebook was a repository for selected poems by favorite authors (e.g. Sylvia Plath); personal reactions to those poems; photos and illustrations cut from magazines and pasted onto the pages; and my own abysmal attempts to write verse. My interest in poetry intensified in college where, as a biology major on the pre-medical track, I took four rigorous poetry courses. During the last of these, in an act of love masquerading as mania, I stopped attending classes, isolated myself from friends, ate and slept reluctantly, and spent five straight weeks writing a metaphysical poem on the theme of subjective vs. objective reality.

What made you pick up the pen again after a 26-year hiatus?

My career in academic medicine was all-consuming. The ten years of post-graduate training and the seventeen years spent as a full-time faculty member at Duke University completely filled my days, nights and weekends. To the extent that creativity was called upon, it was creative problem-solving with respect to patient diagnoses and clinical research. And the papers I wrote and published in the medical literature were strictly factual, analytical and logical.

The instinct to write poetry was completely suppressed throughout this period, but it was not extinguished. As I cut back on my responsibilities during my last year at Duke, that instinct began to slowly reassert itself.

What motivates you to write a poem?

The impulse for me to write can originate from a variety of sources: from a dream; from a vague thought or idea that percolates to the surface from somewhere in the subconscious; from an observation, usually of some natural phenomenon; or from a particularly compelling or disturbing personal experience.

What’s your writing process?

Sporadic and intense.

I have always been undisciplined with respect to writing poems, as evidenced by the fact that I have no set writing schedule. In contrast to many other poets, I lack the ability to sit down daily at my desk and call forth ideas and/or personal experiences to serve as the basis for new poems. Nor have I ever relied on writing prompts. Instead, I wait for lightning to strike (or, mixing metaphors, for the Muse to whisper in my ear). The unpredictability of this approach means that I never know when, or even if, the next poem will materialize.

Once I begin writing, however, I become intensely focused. I often begin as I did in childhood, with pencil and paper. After sketching out a preliminary concept or drafting a few auspicious words or phrases or stanzas, I transition to composing in Word on a laptop.

The key for me is to occupy a mental space where words, sounds, rhythms, and metaphorical possibilities freely and continuously enter the mind, while at the same time applying critical filters to eliminate the 99.9% of options that lack usefulness or merit. Those filters are internal and idiosyncratic. They don’t relate to prevailing trends in poetry or to contemporary poets, though some, no doubt, are subtly influenced by selected works of historical poets.

When fully engaged and maximally productive, I typically write four new lines of poetry per day (derived from perhaps a dozen pages of notes and drafts).

In many of your poems, form seems to play a role. Can you discuss the prevalence of formal elements in your poetry?

Form is as old as poetry itself. It excites the human psyche. Even young children respond to rhyme and repetitive rhythms with joy and the impulse to move in concert with the tempo.

The received form that most commonly appears in my work is the sonnet, probably because of its musicality and because it often surprises the reader with a change in perspective or an unexpected twist at the end. While some of my sonnets obey traditional conventions, others employ more challenging rhyme schemes and/or syllabics (a prescribed number of syllables per line). This raises the stakes, but it also increases the potential for enjoyment if the diction retains its natural inflections and fluidity, the syntax resists distortion, and the formal elements seem to materialize as if by coincidence (what Frost famously described as “riding easy in harness”).

In most of my longer poems, formal elements coexist with free verse. The role of meter and rhyme in these “hybrid” works varies, but includes irony (when blended with darker content), humor, and maximizing the impact of a closing line.

For me, form is paradoxically liberating. Word choices and ideas that never would have bubbled up into consciousness are often evoked by the very constraints that define the form. Indeed, I find free verse much more difficult to write than formal verse, mainly because it mandates that I create the desired semantics, tone, rhythms, and sonic effects organically and without a safety net.

Why are the poems in this collection paired with visual art? How did you select the artwork that would be represented?

The decision to include visual art was an intuitive one. I sensed that many of the poems would resonate in interesting ways with visual images and that this would enhance the reader’s experience.

While a few of the images were selected solely for illustrative purposes (e.g. the image of a goldfinch and coneflower accompanying “Seeds”), most were chosen because they offered alternative slants on the content of the poems. Though the poem “(eclipse)” drips with erotic innuendo, it’s paired with the image of a 1908 patent for an orrery, a mechanical device that replicates the motion of the earth around the sun and the moon around the earth. The sonnet “Nasal Biopsy” is ostensibly about a surgical procedure, but a cathedral door was chosen to accompany the poem because the speaker perceives gothic architecture in the structure of the nose and because the poem is ultimately concerned with questions of faith.

Before writing the poems that appear in “Exits,” did you plan to write a book on the theme of mortality?

No. My initial goal was to curate what I considered to be my best poems from 2003 to 2022 and incorporate that work into a book entitled “Line Drawings.” However, during that process, I noticed that a significant number of the poems were related to one or more aspects of mortality ― disease and decline, death and remembrance. This realization led me to compile a more concise, themed collection of poems, and “Exits” was born.

While writing a poem, do you have an intended audience in mind? Does this influence the content, tone or technical aspects of your work?

The intended audience is always me, or to be more precise, the facsimile of me that constantly looks over my shoulder and critiques every word I write. The word ecstasy comes to mind. It captures the elation I feel when a line finally comes together, but it derives from the Greek ek-stasis ― to stand outside of oneself.

There’s certainly nothing wrong with writing for a defined audience, or respecting the conventions of a particular genre, or exploring themes and issues that currently are in the public eye. My approach happens to be different. What matters most to me are the words on the page, how they sound in air, and whether or not the poem achieves what it set out to achieve.

What do you hope readers will take away from your work?

Enjoyment of the book.

An enhanced interest in form.

Deepened immersion in the concepts of mortality, renewal, and the cycles of life.

Perhaps once in a blue moon, a sense of awe and wonder.

A former award-winning journalist with national exposure, Marissa now oversees the day-to-day operation of the Books Forward author branding and book marketing firm, along with our indie publishing support sister company Books Fluent.

Born and bred in Louisiana, currently living in New Orleans, she has lived and developed a strong base for our company and authors in Chicago and Nashville. Her journalism work has appeared in USA Today, National Geographic and other major publications. She is now interviewed by media on best practices for book marketing.