“Maximum Compound time doesn’t flow; it pools around you, goes stagnant. Each day is similar from the view of a locked world, a day hard and long to get through, and the years flying away.”

NEW YORK – Perpetrator. Bystander. Victim.

NEW YORK – Perpetrator. Bystander. Victim.

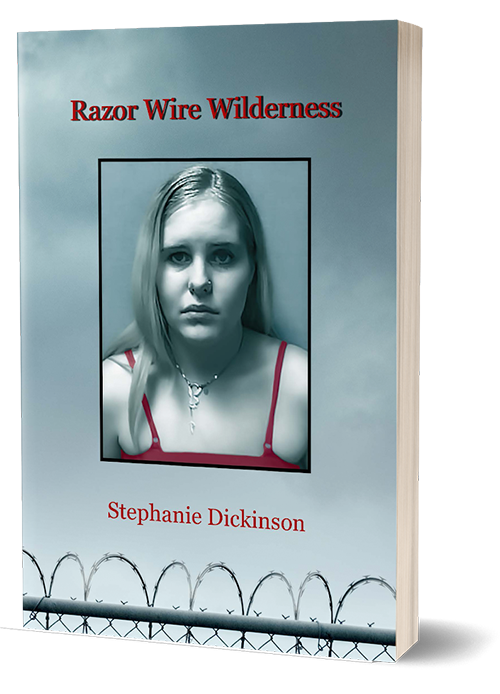

Longtime author Stephanie Dickinson straddles the lines of true crime and memoir in “Razor Wire Wilderness,” (June 1, 2021, Kallisto Gaia Press) as she examines the lives of those affected by violence in this immaculately assembled account that takes readers directly inside incarceration and face to face with inmates.

Krystal Riordan watched as her boyfriend beat a teenage Jennifer Moore to death in a vermin-infested New Jersey hotel room. Could she have stopped it? Or could she be his next victim? Now, Krystal is serving a maximum 30-year sentence, while the man who beat Jennifer to death received only a 50-year sentence. So what does it take to survive in a maximum security lockdown for 30 years? Is it possible to thrive?

The answers only lead to more questions in Dickinson’s raw and emotional look into the criminal justice system and how it’s failed not just one but countless victims of violence. And what unfolds is a beautiful depiction of moral ambiguity, loss and redemption within the confines of the prison walls and beyond.

“Razor Wire Wilderness”

Stephanie Dickinson | June 1, 2021 | Kallisto Gaia Press | True Crime Memoir

978-1-952224-04-1 | Paperback, $21 | Hardcover, $26.45 | Ebook, $8.99

Praise for Stephanie Dickinson

“In the ‘Razor Wire Wilderness’ of Stephanie Dickinson’s exquisitely lyrical portrayal of female incarceration — intimately researched by becoming pen pals with many inmates over many years — she reveals her own dark attraction and identification with Krystal Riordan. … It is not, There but for the grace of God go I,’ but because of Dickinson’s grace and amazing god-given talent that she is able to take us into the heart, mind, memory and imagination of Krystal, passive accomplice to a nightmarish crime. In prison where there is no weather, Dickinson manages to encompass the great Outside; her rendering of Maximum Compound is the opposite of a claustrophobic read. Like Hamlet, bound in a nutshell, Dickinson is king of Infinite space, Infinite empathy, and the Infinite beauty of bad dreams.”

— Jill Hoffman, on “Razor Wire Wilderness”

Mudfish editor and author of “Black Diaries,” “The Gates of Pearl,” and “Jilted”

“Part memoir, part true crime, and part meditation on the resilience of the human spirit, ‘Razor Wire Wilderness is penned with precision and grace.’ Due to Stephanie Dickinson’s unique ability to identify and magnify the personal details that are often unknowingly or willingly overlooked, this book transforms the way we see not only the complexities of a tragic crime but also the way violence becomes embedded in our lives and collective social systems. At its core, this is a story about friendship, but it is also about survival, what happens to us, and what we get to decide during our brief existence. It is about the way we live when we are caged, be that literally or figuratively, and the beckoning light of genuine human connection.”

— Jen Knox, on “Razor Wire Wilderness”

author of “After the Gazebo” and “Resolutions: A Family in Stories”

“Stephanie Dickinson writes with the beauty of a wounded angel. The protagonists in these eleven stories are achingly real, so natural that they craft their own lives. Most, but not all, are women; most, but not all, are young. Each has met humanity’s dark underbelly—through war, predation, neglect, the crueler vagaries of family—and felt the jagged elbows of alienation. And yet, like the ‘Flashlight Girls Run’ of the title, they power on with a particular awkward grace that makes these stories hard to put down, and impossible to forget. Gorgeous, heartbreaking, empowering stuff!”

— Susan O’Neill, on “Flashlight Girls Run”

author of “Don’t Mean Nothing: Short Stories of Vietnam”

“Despite the haunting beauty of Dickinson’s language, naked is possibly the best way to describe her prose. Naked emotion. Naked observation. The warts and the pimples of living presented with the same intensity and honesty as the finely curved hips and thick auburn hair that give life its pleasure. No one writes like Stephanie Dickinson, except maybe God.”

— Alice Jurish

Stephanie Dickinson, raised on an Iowa farm, now lives in New York City with the poet Rob Cook and their senior citizen feline, Vallejo. Her novels “Half Girl” and “Lust Series” are published by Spuyten Duyvil, as is her feminist noir “Love Highway.” Other books include “Heat: An Interview with Jean Seberg” (New Michigan Press); “Flashlight Girls Run” (New Meridian Arts Press); “The Emily Fables” (ELJ Press); and “Big-Headed Anna Imagines Herself” (Alien Buddha). She has published poetry and prose in literary journals including Cherry Tree, The Bitter Oleander, Mudfish, Another Chicago Magazine, Lit, The Chattahoochee Review, The Columbia Review, Orca and Gargoyle, among others. Her stories have been reprinted in New Stories from the South, New Stories from the Midwest, and Best American Nonrequired Reading. She received distinguished story citations in Best American Short Stories, Best American Essays and numerous Pushcart anthology citations. In 2020, she won the Bitter Oleander Poetry Book Prize with her “Blue Swan/Black Swan: The Trakl Diaries.” To support the holy flow, she has long labored as a word processor for a Fifth Avenue accounting firm.

Stephanie Dickinson, raised on an Iowa farm, now lives in New York City with the poet Rob Cook and their senior citizen feline, Vallejo. Her novels “Half Girl” and “Lust Series” are published by Spuyten Duyvil, as is her feminist noir “Love Highway.” Other books include “Heat: An Interview with Jean Seberg” (New Michigan Press); “Flashlight Girls Run” (New Meridian Arts Press); “The Emily Fables” (ELJ Press); and “Big-Headed Anna Imagines Herself” (Alien Buddha). She has published poetry and prose in literary journals including Cherry Tree, The Bitter Oleander, Mudfish, Another Chicago Magazine, Lit, The Chattahoochee Review, The Columbia Review, Orca and Gargoyle, among others. Her stories have been reprinted in New Stories from the South, New Stories from the Midwest, and Best American Nonrequired Reading. She received distinguished story citations in Best American Short Stories, Best American Essays and numerous Pushcart anthology citations. In 2020, she won the Bitter Oleander Poetry Book Prize with her “Blue Swan/Black Swan: The Trakl Diaries.” To support the holy flow, she has long labored as a word processor for a Fifth Avenue accounting firm.

In an interview, Stephanie Dickinson can discuss:

- How the criminal justice system has failed victims of violence — particularly with women and women of color — and what steps can be taken to correct course

- The stigmas surrounding sex work and those who experience sexual violence

- The process of corresponding with inmates in federal prison and the emotional ties formed from connecting with them

- The research conducted for the book and what she learned about U.S. incarceration

An interview with Stephanie Dickinson

1. Can you describe how you first connected with Krystal and when you knew you wanted to tell her story?

In July 26, 2006, Jennifer Moore, age 18, was abducted after a night of underage drinking and taken by small-time pimp, Draymond Coleman, to a seedy Weehawken hotel room that he shared with his sex worker/girlfriend, 20-year-old Krystal Riordan. When I saw Krystal’s arrest photograph, which appears on the cover of “Razor Wire Wilderness,” I knew I wanted to understand her and explore the lethal collision of the worlds inhabited by two young women close in age. I didn’t realize when I first wrote Krystal at the Edna Mahan Correctional Facility for Women in Clinton, New Jersey, that I would tell not only her story but that of life and love in Maximum Compound.

2. How does Lucy’s story connect and intertwine with Krystal’s?

Lucy and Krystal met when they were assigned to the same medical unit work detail that involved caring for a disabled inmate. They were simpatico, Connecticut girls, whose personalities meshed as they worked together, laughed together and eventually bunked together. Corrections officers and inmates alike looked upon them as a package deal. Their pasts mirrored each other: Lucy’s mother abandoned the family when Lucy was 4 years old, (after an aborted kidnapping of Lucy and her brother), while Krystal’s sex worker birth mother neglected her daughters and turned a blind eye to their molestation. And ultimately, both of the women became sex workers.

3. What was the research process like as you were writing the book?

I approached the world of Maximum Compound as a friend and correspondent, primarily interested in Krystal Riordan, and in the process, I learned much about how the corrections facility operates, the thicket of rules I had to negotiate when trying to send a book, the invoices required, the designated months for art supplies. I learned about work details, the pay scale, the Counts, Mess Hall, the Yard, about lovers and friends. My contact with other inmates organically evolved, and I interviewed Lucy Weems at length for months by phone, email and letters. Her keen observation and communication skills were invaluable. Every writer is their own investigative reporter, and research feels like filling the tank and immersing yourself in the place, the lore, the texture, more intimate than the hammering down of facts.

4. In the book, you describe a personal experience with gun violence. How did that encounter affect you, and how do you think it affected how you told these women’s stories?

The tabloids had a field day with the story of Jennifer Moore’s rape and murder: the underage victim, the ex-con assailant, his sex worker girlfriend. I was stunned by the utter waste of it and filled with grief for teenage Jennifer, inebriated, doubly vulnerable, who made the fateful decision to walk off into the night, and grief for Krystal, 20 years old, mesmerized by a violent man who demanded obedience. I, too, made bad choices at age 18, hitchhiking to a distant state to attend a party where a 19-year-old boy brandishing a 12-guage shot me in the neck and face, paralyzing my left arm. So I am aware that the impulsive teenage years are crucial with consequences, and mistakes can last a lifetime as my disability has. I approached Krystal and Lucy’s stories from that perspective.

5. Why do you think the true crime genre has become so pervasive in American culture in the past decade?

In our era of the artificial versus the authentic, sensationalism is fed to us digitally as a substitute for the senses — the taste, touch, hear, see, that evolution gifted us with. We explore cyberspace and grow more removed from the visceral physicality of lived life. The documentary resonates mightily today as does true crime, whether in podcasts, Netflix specials or books. There is an obsession with the real, the actual, and with killers and victims. As human beings, we have a blood lust that at a remove fascinates us, and while we’re glad we’re not the victim, we are drawn to the violent spectacle.

6. Why was it so important for you to tell the world this story?

We tend to judge others in a limited binary fashion, sorting people into categories of good and bad, victims and perpetrators. I’ve inserted myself into “Razor Wire Wilderness” to illustrate the blend of good and bad and the mixed ethical essence in most of us. We are not purely one or the other. In telling Krystal’s and Lucy’s stories, I felt it important to portray their humanity and all of their imperfect stumbling toward the light, even in the darkest of places like prison. To avoid exploitation in my treatment of a real-life crime, I worked to transform the raw tabloid material into a more multilayered narrative.

A former award-winning journalist with national exposure, Marissa now oversees the day-to-day operation of the Books Forward author branding and book marketing firm, along with our indie publishing support sister company Books Fluent.

Born and bred in Louisiana, currently living in New Orleans, she has lived and developed a strong base for our company and authors in Chicago and Nashville. Her journalism work has appeared in USA Today, National Geographic and other major publications. She is now interviewed by media on best practices for book marketing.